|

|

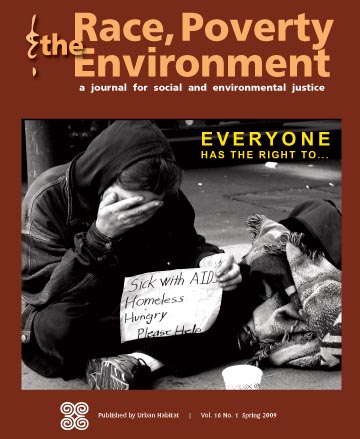

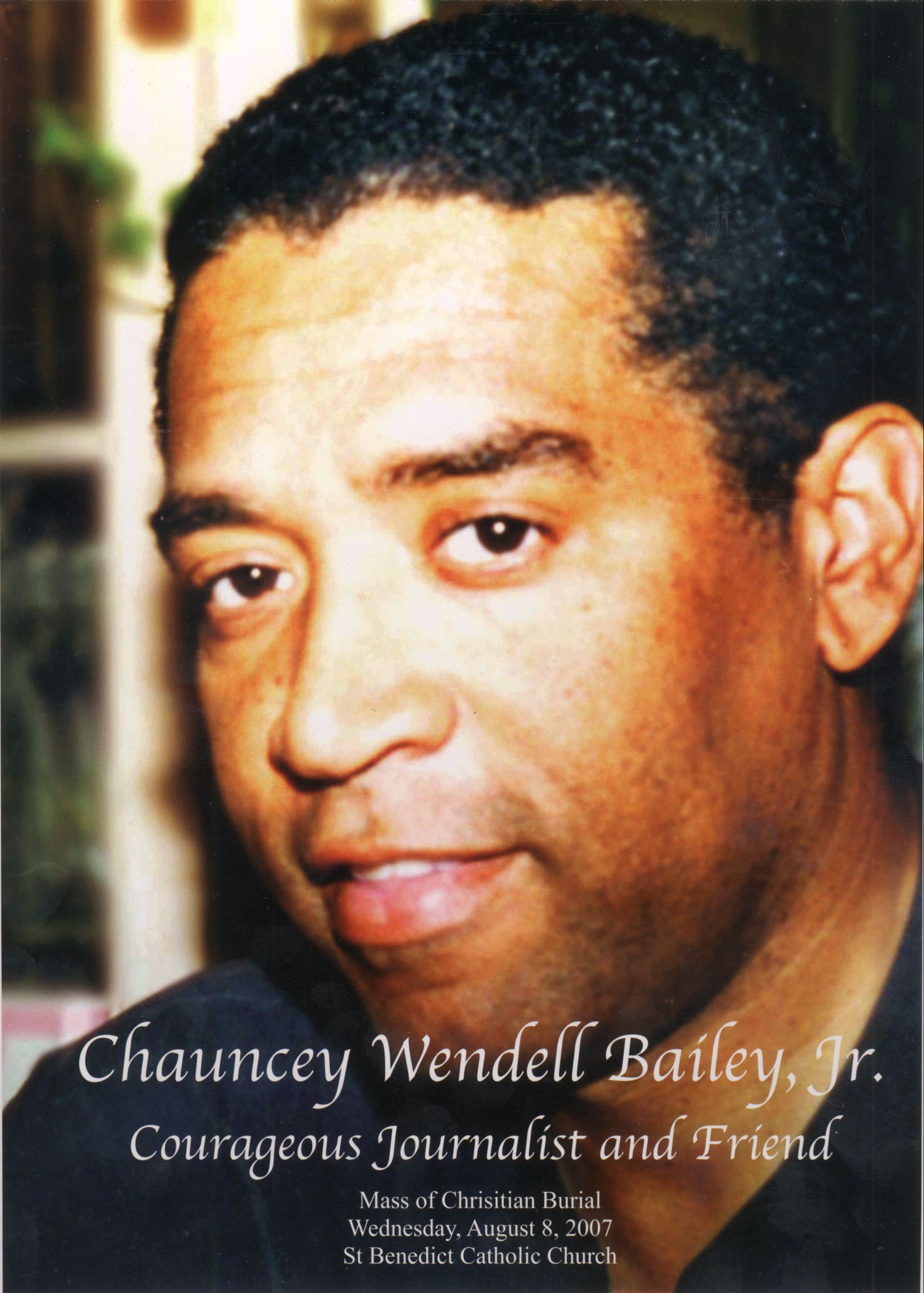

SUGAREE RISING COUNTERPOINTS UNDERCURRENTS I AM OSCAR GRANT ARTICLES FROM RACE, POVERTY & THE ENVIRONMENT PRIDE & PREJUDICE ON REPARATIONS BLACK POLITICAL POWER: Mayors, Municipalities, And Money BRINGING BACK THE BLACK MUDDYING OAKLAND'S WATERS THE VAN HOOL CONNECTION OVERFLOW CROWD MOURNS CHAUNCEY BAILEY AT EAST OAKLAND FUNERAL ARTICLES FROM ALTERNET THE NOTORIOUS S.I.D.

ESSAYS, COVER STORIES AND NEWS ARTICLES FROM METRO NEWSPAPER COVER STORIES AND NEWS STORIES BOOK REVIEWS AND AUTHOR PROFILES FILM, MUSIC AND TELEVISION ARTICLES AND REVIEWS MISCELLANEOUS JOURNALISM OAKLAND UNWRAPPED COLUMNS AWARDS AND RECOGNITIONS CALIFORNIA NEWSPAPER PUBLISHERS ASSOCIATION BETTER NEWSPAPERS CONTEST 1996 Second Place Award, Best Writing 2005 Second Place Award, Columns PENINSULA PRESS CLUB 1997 First Place For Specialty Story Award ASSOCIATION OF ALTERNATIVE NEWSWEEKLIES

1999 Second Place Arts Critcism Award CALIFORNIA TEACHERS ASSOCIATION

CERTIFICATE OF MERIT WINNER

JOURNALIST OF THE YEAR FEEBACK Miscellaneous Reactions To Things I Have Written ATTORNEY GENERAL MOONBEAM?

|

From the Summer 2011 issue of Race, Poverty & the Envioronment

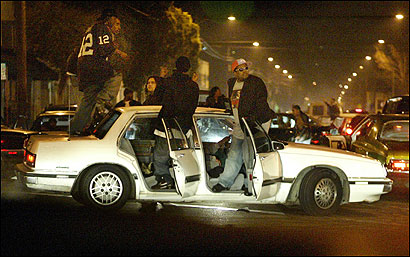

According to the data, Oakland’s African American population plummeted from 142,000 (38 percent) in 2000 to 109,000 (28 percent) in 2010. Even if you included all mixed-race (a new category this census) Oakland residents with some Black ancestry—something which often happens in real life—the number of African Americans in Oakland would only increase by 9,000, or two more percentage points. Both of the Bay Area’s daily papers emphasized the de-African-Americanization of Oakland in their census coverage. The Oakland Tribune story was headlined, “Census: Blacks Leaving Urban Core For East Bay Suburbs,” while the San Francisco Chronicle led with “25% Drop In African American Population In Oakland.” While the actual census figures qualified as news, the trend of African Americans leaving Oakland has been obvious for a while to anyone paying attention. One sign was the growing Black population in North Bay cities like Antioch and Hercules with Oakland exiles. Another was the replacement of African American households with whites over broad swaths of West Oakland and with Latinos in East Oakland neighborhoods. Moreover, it’s hardly a ‘new’ trend in a city once considered ‘Black.’ Oakland’s 30-Year Black Exodus Between 1970 and 1990, Oakland may have actually been a majority-Black city, with the typically undercounted African American population at an official high of 47 percent during the 1980 census. During that period, African Americans also achieved virtual dominance of Oakland’s political offices with a majority-Black City Council and School Board and an African American mayor. But the drop in Oakland’s Black population began in the 1980s. By the time of the 1990 census, the percentage of African Americans was down to 44. The Chronicle speculated that “[a] lower cost of living, the lure of jobs, frustration with schools and the search for safer communities all played key roles” in the Black flight from Oakland. Speaking to the Tribune of a similar trend in nearby Richmond, the Rev. Andre Shumake, president of the Richmond Improvement Association, put it more succinctly: “From what I’ve observed over the past 10 years, I think it’s redevelopment and violence.” By redevelopment, he was referring to the reconstruction of Black neighborhoods in the Richmond and Oakland flatlands, which bumped up housing prices to a point where moderate-income African Americans could no longer afford them. Significantly missing from the list of reasons was Oakland’s uneasy relationship with its African American youth. Many young Black people feel that there is no place for them in Oakland and are moving away as soon as they are old enough to do so. Also missing from the media discussion was the question of what steps Oakland was taking to preserve the diversity that it—quite justly—is so proud of. A Trend Based On Economics Long before the census confirmed what was already known to Oakland’s Black community, political and business leaders had been advancing solutions to the problem. One suggestion was to strengthen the African American business community. Blacks are leaving Oakland because Oakland no longer has jobs for enough of them. Last summer, Oakland political columnist Brenda Payton painted a grim picture of the African American economic situation in Oakland in The Root magazine online. She wrote: “In recent years, the city’s black population has become more stratified, rich and poor, with the middle and working class disappearing... [I]n August the unemployment rate among African Americans was 16.3 percent (compared with 8.7 percent for whites and 9.6 percent overall), 18.8 percent for black males, 14 percent for black females and, among African Americans 16 to 19 years old, an incredible 38.1 percent for females and 51.7 percent for males.” The rapid decline of Black economic power has come as a sudden jolt. “As one older African American man noted,” Payton wrote, “when he was raising his family, he could moonlight at the cannery if he needed some extra money. Young black men and women can’t even find a job, let alone get moonlighting work to earn extra money.”* In a city that has seen its industrial economy virtually vanish, African Americans stand a far better chance of being hired at Black-owned companies than any other small business. “Chinese hire Chinese people, white folks hire white people, Blacks hire Blacks,” said Michael Carter Sr., national chair of Black Wall Street District U.S.A., in a recent interview. “That’s across the board.” Black Wall Street is an Oakland-based national organization that promotes Black business. Pullman Employees Brought Prosperity To Oakland

When the World War II shipbuilding boom opened up jobs to thousands of African American immigrants from the South, West Oakland became their entertainment and cultural center. Black businesses flourished along 7th Street, which became one of the major stopping points for African American entertainers in the middle of the 20th century. People like Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, and Ray Charles graced the hot spots along the street. When the war ended, the African Americans who had migrated west for wartime work moved into Oakland’s booming manufacturing industry. And the sons and daughters of the Pullman porters’ union members formed both the core of Oakland’s dominant Black political leadership of the 1970s through the 1990s, and the leadership of its radical African American organizations, including the Black Panther Party. They also made up the core of Oakland’s Black business owners, which increasingly became the main entry point for jobs for many African Americans coming out of East Bay schools. When Mom & Pop Ruled Oakland Business “I started working at my parents’ record store very early,” said David Reid, owner of Reid’s Records in Berkeley. “I could read record labels before I could read books. I think I was working on Saturdays when I was seven or eight years old.” Reid’s Records was one of the first Black-owned West Coast record stores in 1945. Even when it expanded from its original location on Berkeley’s Sacramento Street Black business center, to satellite stores in Vallejo and downtown Oakland, it remained a Mom and Pop record store. “I had cousins, uncles, great uncles who worked there,” said Reid. “A lot of extended family [who] grew up in the store.” Because of Berkeley’s relatively small African American population, the store depended on Oakland residents for most of its clientele. “We were the place to come to for Black music,” Reid continued. “Because you couldn’t get ‘race music’ in the ‘regular’ record store. [Our stores] were the only outlets [where] African Americans that had newly migrated to the Bay Area [could] get the music they grew up with and knew. We sold a lot of blues. We sold a lot of everything. But in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, the large discount houses started to come to the Bay Area—like Leopold’s, Tower Records, and Warehouse. The mainstream record stores started to get into African American music and sell it cheaper than we could purchase it for. Basically, a lot of our R&B, blues, and jazz clientele left us.” Reid took over the record business from his parents after it compressed back into the single Berkeley store from which it had started. And Reid’s Records, which once hired six or seven people, is now run by Reid and his eldest daughter. Apart from the competition, Reid says his business has also been badly hurt by the Black out-migration. “We seem to get hit the hardest,” Reid said, referring to Black businesses in the East Bay. “We seem to be the ones, when the economy goes down, to really catch hell. I think about the times when if I wanted to go eat some soul food, I had all kinds of places to go to. You have to really dig to find an African American-owned restaurant now—with African Americans who actually cook the food. We don’t even have liquor stores anymore. Or Mom and Pop grocery stores. Or the nail shops. The only thing we probably have are hair stores: barber shops and beauty shops. And churches and funeral homes. That’s about it. Our Black professionals have been assimilated into corporate America.” “We [need] the small Mom and Pops to give these kids jobs, that’s the first line of defense, that’s taking care of our own!” continues Reid. “If we don’t have that kind of support in the Black Community, we’ve seen what it’s done. The Hispanic community has business districts and all kinds of community support and social support. You go to the Asian districts, they have all of this, too. Where is the Black district? The only Black districts we have are where you can go purchase drugs.” Wanted: A Black Business District Black Wall Street’s Carter estimates that there are currently 8,500 African American businesses in Oakland, a steep drop from the 9,800 catalogued by his organization six years ago. But those businesses have no center. Oakland’s core Black business district—7th Street—was broken up during the city’s redevelopment, which began in the early 1960s. Along East Oakland’s International Boulevard, for example, interspersed with the chain stores are shops owned by various ethnic groups. Black Oakland—one of the three largest ethnicities in the city—has no Black business center. Could the establishment of a Black business center in Oakland—like Chinatown or the Hispanic Fruitvale—or even greater support of scattered Black businesses in the city help stem the tide of Black out-migration? Black Wall Street U.S.A. thinks so and, furthermore, believes that it can lead to an economic revival within Oakland’s Black community and the city as a whole. “[Establishing] Black Wall Street in Oakland... is in fact an existing example of how to use recycling of black wealth to better the community,” according to the organization’s 2010 national plan of action. “By supporting local black businesses, black urban neighborhoods can help establish a wealth building system whereby they rebuild themselves internally rather than waiting or relying on external or governmental support.”

|

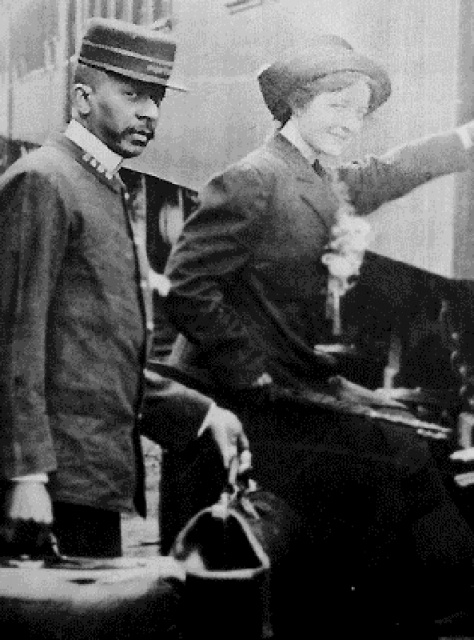

At the turn of the last century, the railroad brought porters and waiters to the Bay Area, all of whom were African American and most of whom settled in West Oakland, near the station that marked the end of the railroad lines. The railroad workers—helped enormously by the economic benefits gained from their hard-fought union contract with the Pullman rail car company following a national strike—formed the core of Oakland’s rising Black middle class. They bought homes in West Oakland and opened businesses. C.L. Dellums (uncle of former mayor Ron Dellums and one of the founders of the railroad porters’ union) operated a West Oakland pool hall that became the congregating point for many famous African American entertainers, including Bill “Bojangles” Robinson.

At the turn of the last century, the railroad brought porters and waiters to the Bay Area, all of whom were African American and most of whom settled in West Oakland, near the station that marked the end of the railroad lines. The railroad workers—helped enormously by the economic benefits gained from their hard-fought union contract with the Pullman rail car company following a national strike—formed the core of Oakland’s rising Black middle class. They bought homes in West Oakland and opened businesses. C.L. Dellums (uncle of former mayor Ron Dellums and one of the founders of the railroad porters’ union) operated a West Oakland pool hall that became the congregating point for many famous African American entertainers, including Bill “Bojangles” Robinson.