Homepage of J. Douglas Allen-Taylor, Jesse Taylor, Doug Allen, Douglas Paul Allen, and other names either long forgotten, best forgotten, or too numerous to mention |

Safero (sa-fe'-ro) "the act of writing" |

FAMILY PAGES

SUGAREE RISING

COUNTERPOINTS

ANYBODY BUT PERATA

HOW VERY JERRY

WRITING PAGES

THE GONEWAYS

Contact Me

|

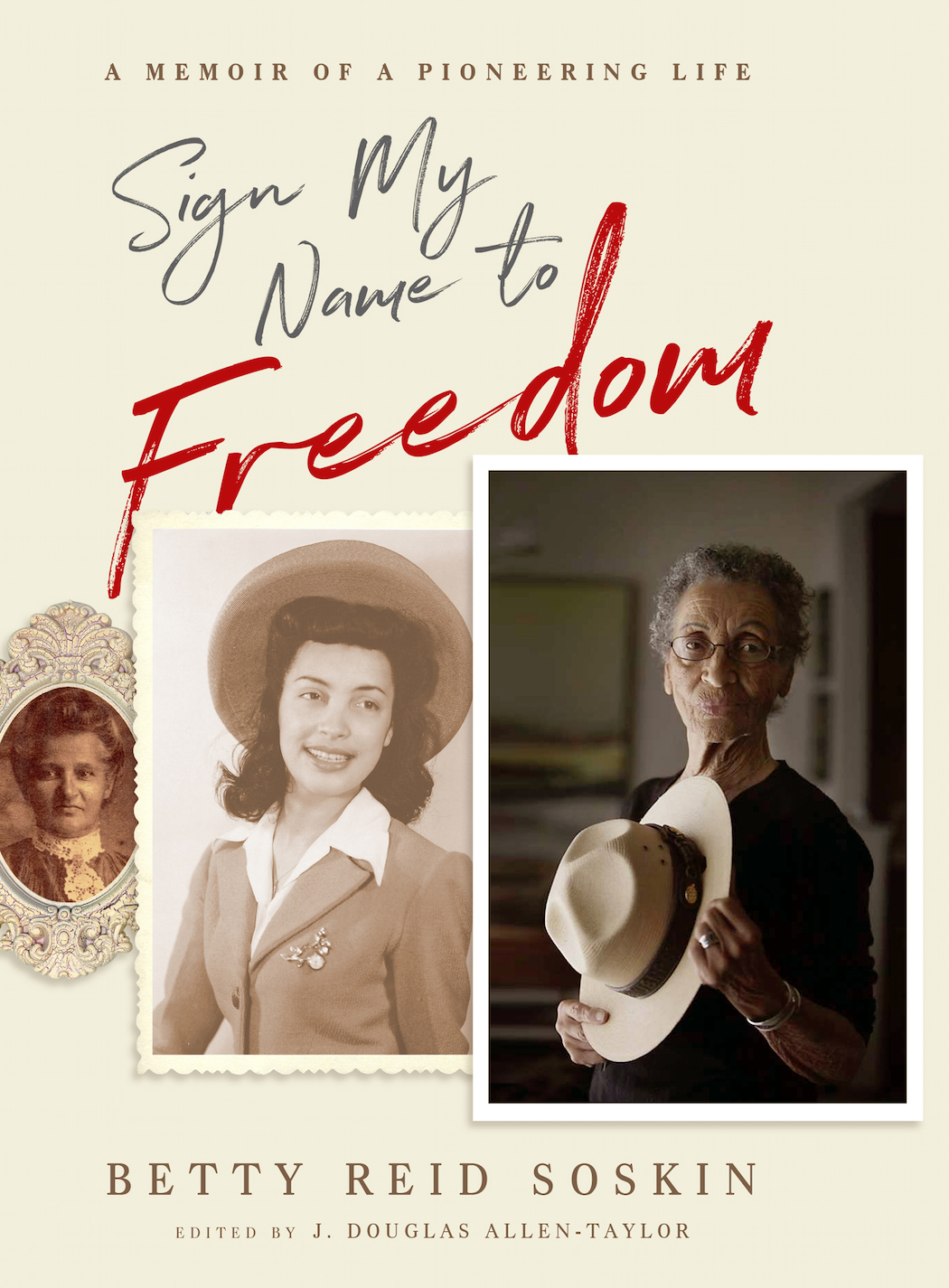

Two New Books Edited By J. Douglas Allen-Taylor

Betty Reid Soskin's New Autobiography Captures An Astonishing Life

Betty Reid Soskin remembers the days when young women of color had three choices in life: "One, working in agriculture; two, being a domestic servant; or three, marrying well," the 96-year-old interpretive ranger told an audience at Richmond's Rosie the Riveter museum. Her voice breaking, an African-American woman in attendance told Soskin, "My grandmother is 94, and she still sees those choices as the only ones. I wish she could be here today." "I wish she could be, too," Soskin responded softly. Soskin refers to those "choices" in her lectures at the museum, and in her newly published autobiography, Sign My Name to Freedom: A Memoir of a Pioneering Life. But as the woman in the audience, and readers of the book, quickly learn, for Soskin, those choices were far from enough. Local legend, national treasure, and force of nature, Soskin describes her multifaceted journey in her book: "It's like reincarnation without ever leaving." [To Complete Review]

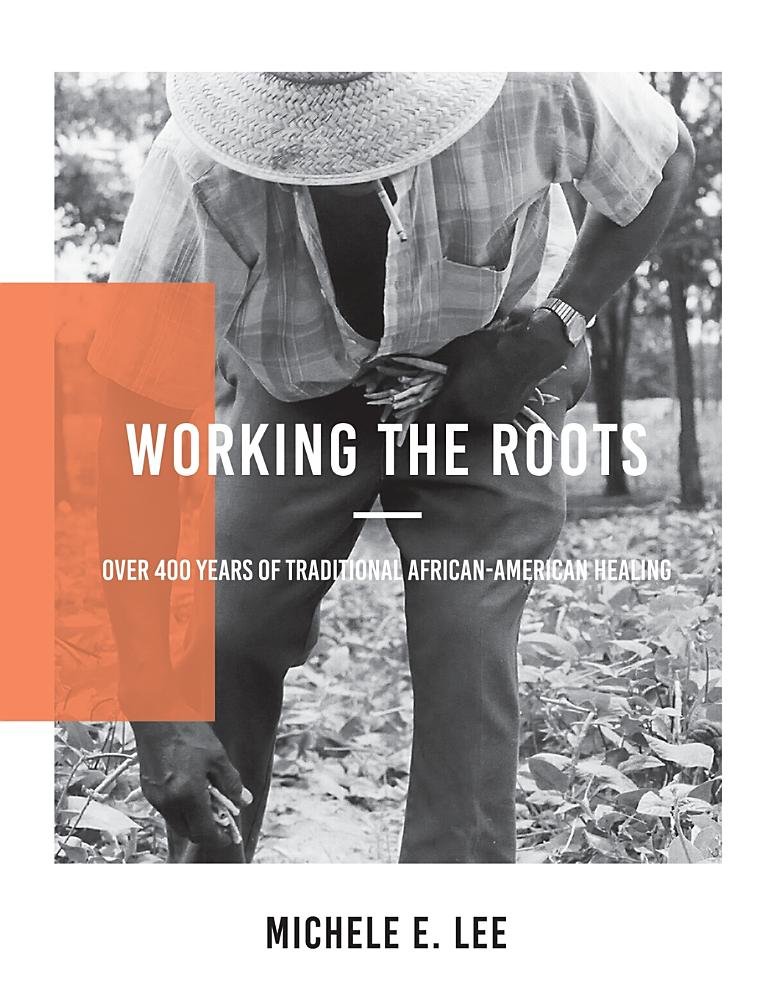

"Working The Roots" by Michele E. Lee

African American traditional medicine is an American classic that emerged out of the necessity of its people to survive. It began with the healing knowledge brought with the African captives on the slave ships and later merged with Native American, European and other healing traditions to become a full-fledged body of medicinal practices that has lasted in various forms down to the present day. Working the Roots: Over 400 Years Of Traditional African American Healing is the result of first-hand interviews, conversations, and apprenticeships conducted and experienced by author Michele E. Lee over several years of living and studying in the rural South and in the West Coast regions of the United States. She combines a novelist's keen ear for storytelling and dialogue and a healer's understanding of folk medicine arts into a book that makes for both pleasant, interesting reading, and serves as a permanent household healing guide. Divided between sections on interviews of healers and their stories and a comprehensive collection of traditional African American medicines, remedies, and the many common ailments they were called upon to cure, Working The Roots is a valuable addition to African American history and American and African folk healing practices.

What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk February 14, 2018 On the morning in the fall of 2015 when I heard about the argument and physical confrontation between former Black Panther chairperson Elaine Brown and Oakland City Councilmember Desley Brooks—two prominent Oakland African American women leaders—down near Jack London Square, I could only shake my head and say to myself that regardless of which one of the women got the blame and who was actually at fault, this was going to end up being bad for Black Folk in Oakland and the Bay Area as a whole. Nothing that has happened since then has changed my opinion. Let’s try to sort out as much as we can, in order to explain why I feel that way. Two years ago, Ms. Brown was seeking public assistance for her Oakland and World Enterprises non-profit organization—including land from the City of Oakland—in creating an affordable housing complex in West Oakland dedicated to formerly-incarcerated persons. On October 30th of that year, by all accounts, Ms. Brown and Ms. Brooks got into a argument at Everett & Jones Restaurant near the Oakland waterfront after Ms. Brooks indicated that she would oppose the proposed land deal with Ms. Brown’s organization. The argument turned heated, and ended with Ms. Brooks pushing Ms. Brown, causing the former Panther leader to fall and sustain injuries. Ms. Brown says the pushing was unprovoked. Ms. Brown says she was defending herself from an attack by Ms. Brooks. Ms. Brown eventually sued both Ms. Brooks and the City of Oakland in civil court, winning a more than $4 million verdict that is mostly charged to the city. Other than who was at fault in the shoving incident, all of these facts are uncontested by either side in the dispute. [To Complete Column]

What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk, Part 2 February 27, 2018 When we were last all together, we were beginning a discussion about the repercussions coming out of the 2015 argument and physical confrontation between Oakland City Councilmember Desley Brooks and former Black Panther Party Chairperson Elaine Brown. It’s a complicated issue that can’t be summed up in 280 characters on Twitter, or in this case, even a single thousand-word column. So if you’re looking for quick answers, or answers without the benefit of context, you’ll have to look elsewhere. This ain’t that kind of party. But if too much word count is a worry for you, I won’t review what was already talked about in the original column; you can review it yourself (“What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk”). I’ll only say that my premise in that first column was that “regardless of which one of the women got the blame and who was actually at fault [in the confrontation], this was going to end up being bad for Black Folk in Oakland and the Bay Area as a whole.” Meanwhile, we’ll continue where we left off, with the San Jose Mercury News/East Bay Times publishing a joint editorial in January calling for voters in Oakland’s Council District 6 to turn Ms. Brooks out of her City Council office in next November’s election because of what the editors called the Councilmember’s pattern of “abuse of power.” A collection of members of the Oakland City Council weren’t content to wait that long, however, for Ms. Brooks to be punished for what these Councilmembers perceived as her political and personal transgressions. Neither did these Councilmembers care to leave that punishment in the hands of District 6 voters. So last month, resolution was introduced for City Council consideration with the somewhat bland title of “Adopt A Resolution Amending Council Rules Of Procedure ... To Authorize The Council President To Change Committee Membership And Committee Chair Assignments” that many observers felt was aimed directly at taking a considerable block of power away from Ms. Brooks. [To Complete Column]

What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk, Part 3 March 14, 2018 We have been talking about the aftermath of the 2015 altercation between two prominent Oakland African-American women leaders, Oakland City Councilmember Desley Brooks and former Black Panther Chair Elaine Brown. In the first two installments of this discussion, we discussed how the blows thrown in the weeks and months after that altercation were struck most heavily against Ms. Brooks. First, Ms. Brown filed a lawsuit against Ms. Brooks and the City of Oakland that eventually won her a more than $4 million jury verdict late last year. Following that verdict, Ms. Brooks was loudly vilified in the local media with calls for her defeat and ouster from the City Council in the upcoming Council elections. More ominously, a coalition of Oakland City Councilmembers made the first legislative moves in what at least one Councilmember (Annie Campbell Washington) admitted was a campaign to strip Ms. Brooks of her influential position as chair of the City Council Public Safety Committee. (See “What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk” and “What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk, Part 2”) But “blows struck most heavily” against Ms. Brooks does not mean “blows struck exclusively.” In fact, as far back as two months following the altercation between the two women at Everett & Jones Barbecue Restaurant in the Jack London Square area of Oakland, then-San Francisco Chronicle East Bay columnist Chip Johnson was already using the altercation to tear down both women. Interestingly, the Chronicle columnist did not go after Ms. Brown initially. His first shots were fired exclusively at Ms. Brooks, with whom Mr. Johnson had engaged in a running public feud for several years. [To Complete Column]

What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk, Part 4 April 2, 2018 This is the fourth in a series of columns about the fallout from the 2015 confrontation between Oakland City Councilmember Desley Brooks and former Black Panther Party chair Elaine Brown and what the negative effects from that confrontation means for Black Folk as a whole in Oakland and the Bay Area. If you need to get caught up, see “What Brown V. Brooks Means For Black Folk,”“What Brown V. Brooks Means For Black Folk, Part 2,” and “What Brown V. Brooks Means For Black Folk, Part 3”. We left off our last discussion of the fallout from the Brown v. Brooks confrontation with a February column by San Francisco Chronicle’s Phillip Matier and Andrew Ross clearly written to cast doubt on Ms. Brown’s contention—and an Alameda County Civil Jury’s conclusion—that Ms. Brown suffered an unprovoked physical attack at the hands of Ms. Brooks at the Everett & Jones Barbecue restaurant in the Jack London District of Oakland in the fall of 2015. (“Break For Ex-Panther Who Sued Oakland: Jury Didn’t Hear About Other Dustups” San Francisco Chronicle February 10, 2018) The longtime Chronicle columnists—known jointly as “Matier & Ross”—are among the most well-connected journalists in the Bay Area, with close ties to the corporate and political elites of this area. Much of what they write in their various columns seems designed to either influence where they want that establishment community to go, or else to give insight into where that establishment community is already going. And so it shouldn’t be absolutely surprising that the columinists used that recent “Break For Ex-Panther” column to try to trash the actions and reputation of Elaine Brown. The former Panther leader has collected her fair share of powerful establishment enemies over the decades, and there are many in high places who have a long and vested interest in preventing her from ever rising again as an influential leader within Oakland and the nation’s newly-rejuvenated Black Movement. [To Complete Column]

What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk, Part 5 This is the fifth in a series of columns about the fallout from the 2015 confrontation between Oakland City Councilmember Desley Brooks and former Black Panther Party chair Elaine Brown and what the negative effects from that confrontation means for Black Folk as a whole in Oakland and the Bay Area. If you need to get caught up, see “What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk,”“What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk, Part 2,” and “What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk, Part 3,” and “What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk, Part 4.” April 17, 2018 “If a guy's close to you, you can't slight 'im. You can't slight that guy. A real grievance can be resolved. Differences can be resolved. But an imaginary hurt, a slight—that [mf] gonna hate you 'til the day he dies.” -- Jimmy Hoffa in the movie Jimmy Hoffa In order to fully understand the implications of the beef between former Black Panther chair Elaine Brown and Oakland City Councilmember Desley Brooks, we need to go back in time a bit. Bear with me. In the long history of the Black Freedom Movement in America, just as in the movie Jimmy Hoffa quote above, political differences have always been far easier to overcome than personal ones. While the Movement has often disagreed over where African-Americans should be going and how we should get there, we have often been able to put those differences aside to build temporary coalitions on matters of overwhelming import to the race: the coalition in support of the Scottsboro Boys in the 1930’s, or the creation of the Montgomery Improvement Association that led the 1956 Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott, the 1963 March on Washington, the 1966 Mississippi March Against Fear that spawned both the Black Power movement and spurred Martin Luther King’s public opposition to the war in Vietnam, the 1967 Newark, New Jersey Black Power Conference, the 1972 Gary, Indiana National Black Political Convention, to name only a few more recent examples. Settling personal differences within the Black Movement, on the other hand, has always been more elusive, with jealousies and animosities more often than not overwhelming the need to come together for the greater good. But sometime beginning in the late 1960’s, for reasons we only began to understand much later, and too often too late, those personal differences began to become both more common, more prominent, and more difficult to settle. [To Complete Column]

What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk, The Conclusion May 8, 2018 Much has happened around the Brown v. Brooks matter since we were last all together, but the basic dynamic we’ve outlined in the first five parts of this “What Brown v. Brooks Means For Black Folk” (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5) have remained basically the same. In the political, media, and legal battle between Elaine Brown and Desley Brooks that has grown out of the original 2015 physical confrontation between the two women at Everett & Jones in Oakland’s Jack London Square—the blows have continued to fall the most heavily on Ms. Brooks. Earlier this year, for example, Otis R. Taylor Jr., who took up the San Francisco Chronicle’s East Bay columnist seat from our old friend, Chip Johnson, also took up Mr. Johnson’s longtime campaign against Ms. Brooks by calling the District 6 Councilmember Oakland’s “version of Donald Trump” in a January 30 column. Ms. Brooks is “dismissive during public meetings, peering through the eyeglasses propped on the bridge of her nose like a derisive schoolmarm,” Mr. Taylor begins his list of grievances against the Councilmember. “She exudes contempt for people who dare offer an opinion that conflicts with her own. She seems to speak only to her base supporters, those who agree with her messages no matter how unreasonable she sounds from her pulpit.” (“Oakland City Council has its own Donald Trump” San Francisco Chronicle January 30, 2018) How the above examples, or any of the rest of the complaints Mr. Taylor presents in his “Oakland City Council Has Its Own Donald Trump” column, actually show that Ms. Brooks has taken any actions in her Council career even remotely similar to those of the U.S. President seems to be a bit beyond my level of comprehension. But equating someone to the much-hated Donald Trump has become a popular—if lazy—way to slur someone in our community, so I suppose we ought to get used to it. And so, right on schedule, Mr. Taylor’s Brooks-as-Trump theme was taken up and embellished only a few months later by Oakland Mayor Libby Schaaf, in a press conference announcing the mayor’s opposition to Ms. Brook’s re-election to City Council. CBS Local quoted Ms. Schaaf as making the claim at that April press conference that “[o]ne individual, more than any, someone who’s been nicknamed the Donald Trump of Oakland, who has engaged in unethical and abusive behavior has had a true impact, a ripple effect that really has infected the civility of the council chambers, as well as the professionalism of our city workers.” (“Mayor Schaaf Says Councilwoman Dubbed ‘Trump Of Oakland’ Must Go” CBS Local April 13, 2018) [To Complete Column]

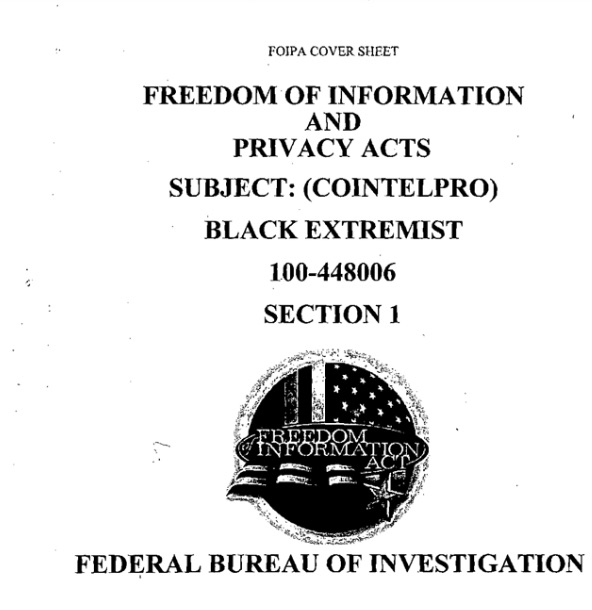

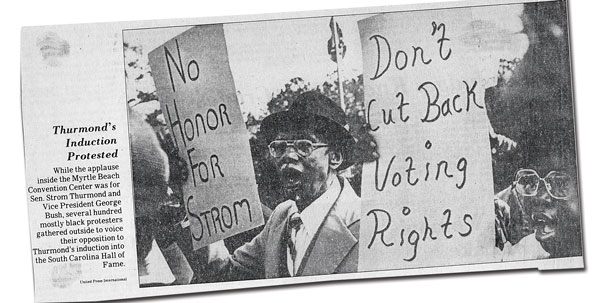

Defeating Strom

By the fall of 1980, Strom Thurmond's opposition to the 1965 Voting Rights Act was well-documented and well-known. He had fiercely fought against it 15 years before, saying its passage would "destroy the provisions of the Constitution [and lead to] a totalitarian state in which there will be despotism and tyranny." U.S. Sen. Thurmond lost that argument badly that year, with the Act passing the Senate on a 77-19 roll call vote. It was later passed by the House and signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson. However, 15 years later Thurmond renewed his effort to kill the law. By 1980 both the nation and the Senate had changed radically. Republicans had gained control of the Senate in the Reagan landslide election that November, and Thurmond was set to take up the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, which had jurisdiction over the Voting Rights Act. More importantly, the act's critical Section 5 "pre-clearance" provisions were set to expire in 1982. These provisions were the heart of the Voting Rights Act, and they required states covered by the law — mostly those in the Deep South — to ask for U.S. Justice Department approval before changing election laws. With the Senate in Republican hands and a conservative Republican President Reagan presumably waiting with a veto pen in hand, Thurmond's road to victory seemed clear and open. A year and a half after Thurmond declared war on the Voting Rights Act, the Senate voted 85-8 to renew it and the Section 5 provisions, joining the House of Representatives. Thurmond was even one of the 85 aye votes in the Senate. After that, President Reagan signed it into law. What forced Thurmond to change his position was partially the work of a small group of South Carolina black rights activists who took up the battle and created a statewide movement to save the Voting Rights Act. They were joined by thousands of black South Carolinians who had only recently acquired full voting rights. Together they defeated Thurmond in his own state. [To Full Article]

|