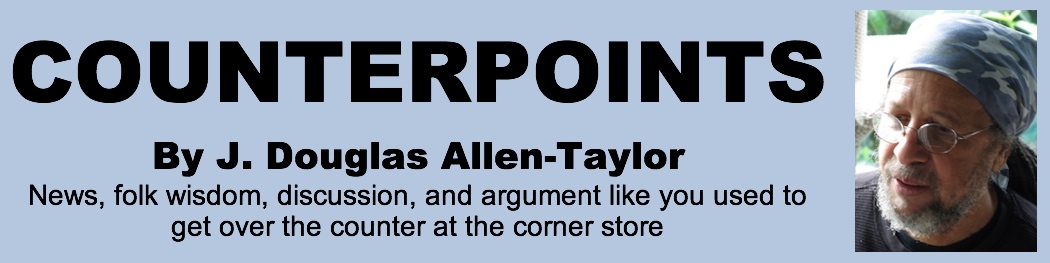

Tom Reid Sr. and Jenny Parker Reid with children Florence and Bob on the porch of their Berkeley home

The History Of Black History At The Berkeley Historical Society

November 17, 2021

Does the real history of Black People—which includes the real history of racism against Black People in Berkeley—matter to the operators of the Berkeley Historical Society? Or are they hiding a good portion of that history because it goes against the long-held belief of a progressive, diverse-friendly Berkeley?

After years of missteps and neglect in chronicling the history of Black People in Berkeley, the curators and officials at the Berkeley Historical Society—located in the massive former Veterans Memorial Building in middle of the city’s downtown civic square—are trying to convince us these days that this time, at least, they’re trying to get it right.

As for me, based on recent less-than-favorable experiences with the Historical Society, I still need a bit more convincing.

“Founded in the summer of 1978,” according to its website, the Berkeley Historical Society “is a non-profit, all volunteer group dedicated to researching, preserving and sharing Berkeley’s history. Through exhibits, lectures, walking tours and publications, an appreciation for the uniqueness of the city and the diversity of cultures that comprise the rich mosaic of Berkeley has been fostered and recognized.”

Going along that whole diversity of cultures thing, the Society announced late last summer that they were “hosting the second exhibit in a series curated by Dr. Stephanie Anne Johnson and Harvey Smith highlighting historical figures and establishments in Berkeley’s Black Community during the years 1940-2000. Through detailed maps and photographs, this year’s exhibit focuses on businesses, politics, education, social organizations, and religious institutions, honoring and uplifting the community’s experiences, contributions, and legacies.”

The Historical Society’s “African Americans In Berkeley” exhibit was scheduled for online presentation and personal view through the end of October.

The impetus for this current interest in the history of Black People in Berkeley goes back to the Berkeley Historical Society’s 40th Anniversary Celebration in May of 2018, where they asked nationally-known National Park Ranger Betty Reid Soskin to be the keynote speaker. While Betty was raised in Oakland and currently lives in Richmond, she spent many years as a Berkeley resident, business owner, legislative aide, and social and political activist, and is therefore closely associated with Black Berkeley history.

But it seemed that the Historical Society needed a little more from Cousin Betty than just a speech.

A month before the celebration, one of the Society’s representatives emailed Betty with the following: “The Berkeley Historical Society was wondering if you have a few [pictures] of your family life in Berkeley. Perhaps your family by your house or the Reid family interacting and also some pictures of the record store? San Pablo Park? Would you be willing to share some [pictures] with [the Berkeley Historical Society] for use in our upcoming exhibit and also in our collection.”

The record store referred to in the email was Reid’s Records, founded by Betty and her first husband, Mel Reid, just after World War II in the heart of what was then Berkley’s popular Sacramento Street Black business district. Reid’s was one of Berkeley’s most important and long-lasting Black-owned businesses, selling blues, rhythm & blues, and gospel records by Black artists during the years that such recordings were generally unavailable in other Bay Area record stores. As for San Pablo Park, the large outdoor and indoor recreation area still located in West Berkeley, it was one of the most important sports, recreation, and social gathering places for Black People in the East Bay in the 1920’s and 1930’s. It was odd, therefore, that after 40 years of existence, an official organization dedicated to preserving and presenting the history of Berkeley didn’t already have photographs of two iconic portions of Black Berkeley history from the last century.

Children's presentation at San Pablo Park in Berkeley, circa 1933—Hazel and Maybelle Reid (daughters of Thomas Sr. and Jenny Reid) third and second from right, Muriel Reid (granddaughter of Thomas Sr. and Jenny Reid, daughter of Thomas Jr. and Reba Reid) far right. This photograph was retrieved online simply by doing a Google search of the term "San Pablo Park Berkeley"

Betty and I are cousins on my father’s side, and her first husband, Mel, was my mother’s nephew. Over the years, we’ve worked together on many family history projects for both sides of our families, and therefore she knew that I had access to a large collection of Reid family photos. She asked me for help with providing what the Berkeley Historical Society had asked for.

The Reids, were an important part of Black Berkeley history and life.

Thomas Reid Sr. and Jenny Parker Reid—my grandparents and Mel’s—migrated to Berkeley sometime around 1905. They had 13 children, 10 of whom were born in Berkeley, 11 of whom survived to adulthood. All of the surviving children grew up in Berkeley, and many of them lived out their entire lives there. Thomas and Jenny’s second son, Charles Reid Sr., was an amateur photographer who took hundreds of snapshots of the Reids and their Black Berkeley friends from around 1914 through the early 1920’s. Along with Uncle Charlie’s photos, the family maintains several private collections of other family photos that comprise an important look into Black Berkeley life in the first half of the 20th century.

Portrait of Reid family members and their friends, Berkeley, California, circa 1922

At Betty’s request, I put together several of these photo scans and emailed them to the Berkeley Historical Society for display at their 40th Anniversary Celebration to supplement what Betty provided and what they already had on hand.

It’s a good thing that the Reid photographs were provided. That’s because the photographs of Black Berkeley People in the Berkeley Historical Society’s official display of Berkeley history available at the anniversary celebration, well, left a lot to be desired, to put it politely.

The Historical Society’s photos were presented in what they called the “Timeline Of Berkeley History.” The Timeline was mounted on a series of moveable display boards set up in the office reception area of the Society’s headquarters. The main section was made up of an actual timeline of photographs and text of Berkeley history in two panels, beginning around 3700 BCE with the First Nations Shellmound builders who originally inhabited the area, ending in 2017, the year the Timeline was created. Accompanying the two main Timeline panels were a series of supplemental panels illustrating different specific aspects of Berkeley history. These had all been prepared and mounted well before the Society had received the photographs that were sent them from the Reid family. The Reid photos were displayed on a counter behind the Timeline and its supplementary panels and separate from them.

Viewing Timeline of Berkeley History panels at Berkeley Historical Society 40th anniversary

Folks who attended the anniversary celebration were encouraged to walk around the lobby reception area to view the Timeline display. I glanced at some of them, but it was the supplementary panel depicting “Family Life In Berkeley” that got my attention. As far as I remember, there was only one African-American posted among the pictures on this Family Life panel, a young Black boy playing in the street with what looked like a group of either Filipino or Latino youngsters. That was it, the extent of what the Berkeley Historical were presenting as Black family life in Berkeley.

I was appalled, to say the least, because for me, Berkeley was synonymous with Black family.

I grew up in Oakland, but as a youngster, I often went over to Berkeley. When I did during those days in the 1950’s, it was almost always to visit Reid family members with my mother. I took one of the rites of passages of many of the Reid cousins, to be dropped off to be babysat at the Berkeley home of Aunt Bert, who was then the matriarch of the Reid clan. Later, as I grew a little older, it was sometimes to play with cousins while my mother spent the afternoon chatting with one of her sisters. Sometimes we stopped at Mel and Betty’s shop to pick out a record. But the best visits were on Christmas eve, when we went around to all the Reid homes in Berkeley to exchange presents. The last stop that evening was always at Aunt Bert’s, where many of the Reid family members gathered for food, fun, and fellowship.

At the Christmas eve gatherings at Aunt Bert’s, after the traditional holiday turkey dinner and the downing of punch and eggnog, Aunt Ruth was guaranteed to performing, dancing the hula, playing a ukulele, and singing Hawaiian songs. With no children of her own, she was nevertheless the favorite of the younger Reid cousins, as she could always be guaranteed to pull the youngsters in the corner to spill family secrets that the other family elders would never tell us, hushing up only with a whispered, “Uh-oh, here come the judge,” if her older sister, Aunt Bert, happened by.

Cousin Mel, who was probably the best athlete in a family full of good athletes, was always full of stories and jokes. One of my favorites was the time some of the older family members were talking about the photographers who used to come around Berkeley in the older days with their ponies and carts, soliciting parents to purchase pictures of their little children sitting in the pony cart. Mel shook his head and said that was for the families with money; the Reids in the old days, he assured we youngsters who were listening, were too poor to afford pictures in the pony cart. The Reid kids had to wait for the man with the goat cart, who charged considerably less. I thought this was just one of Cousin Mel’s made-up jokes, until one afternoon when I came across an old picture of a very young Mel and my very young mother in a goat cart. I burst out laughing when I saw the picture, as I still do whenever I see it still.

Cousin Mel, who was probably the best athlete in a family full of good athletes, was always full of stories and jokes. One of my favorites was the time some of the older family members were talking about the photographers who used to come around Berkeley in the older days with their ponies and carts, soliciting parents to purchase pictures of their little children sitting in the pony cart. Mel shook his head and said that was for the families with money; the Reids in the old days, he assured we youngsters who were listening, were too poor to afford pictures in the pony cart. The Reid kids had to wait for the man with the goat cart, who charged considerably less. I thought this was just one of Cousin Mel’s made-up jokes, until one afternoon when I came across an old picture of a very young Mel and my very young mother in a goat cart. I burst out laughing when I saw the picture, as I still do whenever I see it still.

The Reids were a family of musical talent, and most of them played an instrument of some sort. Aunt Bert had a piano in her parlor, and Uncle Paul would often sit down to it and play carols while family members joined in. Uncle Paul was a gospel deejay and promoter, so beloved in the Bay Area’s black church community that when he passed away, only the Oakland Auditorium was large enough to accommodate the funeral.

Uncle Bob must have played the saxophone at one time because I’ve seen a picture of him with one hung from his neck, though I never heard him play one myself. His major claim to fame as a youngster was that he was good friends with Johnny Otis, the Greek-storeowner’s-son-turned-African-American-bandleader-and-composer (true story) who was one of the main drivers of Black music in the middle of the last century. Otis told me once, later in his life, that Uncle Bob would have loved to join his band, but though he was an enthusiastic sax player, he just didn’t have the talent necessary to become a professional musician. Uncle Bob didn’t have the talent to become a professional athlete either. His special talent was the mentoring of youngsters, particularly those in the family. One of his protégés was Phil Chenier, who played basketball at the University of California at Berkeley and later in the NBA with the Washington Bullets, later the Wizards. After he passed away, my mother and I were tasked with going through Uncle Bob’s things left in his Berkeley apartment. We were surprised to find a scrapbook in which, over the years, he had faithfully collected the newspaper clippings of all the family children who played high school ball, including one of my own daughters, who had been a soccer player in school.

This, to me, was Berkeley. And family. And Black.

Fourth of July gatherings of the Reid family were regularly held for a time at the home of our Uncle Tom, the oldest of the children of Tom Sr. and Jenny, so different from the Uncle Tom of Harriet Beecher Stowe creation, who had moved across the hills to Danville to a small ranch. These gatherings were synonymous with barbecue, a huge bowl of Louisiana-style homemade potato salad, red Kool-Aid in a big pitcher, and a phonograph player someplace in the house piping out Ray Charles or Nat King Cole over the back yard. After Uncle Tom passed away, the summer gatherings moved to the Concord home of Mel and Betty and then, later, to my parents’ home in Oakland. But wherever in the East Bay they were held, memories of old Berkeley were always at the center of it. For those of us youngsters who were not yet born when the family had moved into Berkeley from the Sierra gold country, or from Georgia and Virginia before that, we always saw Berkeley as the family’s ancestral home.

Women of the Reid family gathering on the 4th of July at the Allen home in Oakland

But to be a member of the Reid family was not just to be connected to the large and growing Reid family itself, but also to be immediately intertwined with many other Black families with Berkeley roots, Black pioneer families or “old-timer” families, so they called themselves, the Black families who had come to the East Bay long before the Great Black Migration out of the Deep South during the World War II years. For a long time these Black East Bay pioneer families held an annual summer at Lake Temescal in the East Bay hills. The Old-Timers Picnic, they called it. Most of these old-timer families had actually lived in Berkeley itself one time, or else had come regularly to Berkeley to shop at the city’s Sacramento Street Black business district, or to hang out at San Pablo Park.

So I was understandably disturbed and felt personally disrespected by the lack of Black representation in the Berkeley Historical Society’s depiction—or lack of depiction—of Black People in its Berkeley Family Life display. How could they have possibly missed all of that rich history? Bob Reid, one of Mel and Betty’s sons, was present at the 40thAnniversary celebration, and if memory serves, both he and I voiced our concerns to Historical Society officials about the Family Life display. I know I did.

Much later, long after the anniversary celebration was over, I had the chance to more closely review online the items in the main Timeline Of Berkeley History panel that I had only looked over briefly at the anniversary celebration itself. During that review, I discovered that its depiction of the history of Black People in Berkeley was just as distorted as the Family Life panel, maybe worse. While a detailed review of the distorted Black history in the Historical Society’s main Timeline panels is necessary, it would be too long to be included in this essay, and will have to wait for another time.

In any event, the discussions with Society representatives on the day of the 40th Anniversary celebration over concerns about the Family Life panel evolved into a series of conversations between myself and Historical Society representatives over the next several months. The consensus of those informal discussions was that the Society had done a generally poor job of presenting Black Berkeley history, and the focus was how to correct the problem.

After some twists and turns, these informal discussions eventually led to Society suggesting the creation of what it called the “African Americans In Berkeley: Four Families.” The Four Families exhibit eventually opened in October of 2019.

After some twists and turns, these informal discussions eventually led to Society suggesting the creation of what it called the “African Americans In Berkeley: Four Families.” The Four Families exhibit eventually opened in October of 2019.

The consensus in our discussions had been that Black life in Berkeley should eventually be fully integrated into every aspect of the Historical Society’s presentations of Berkeley history, but it was also acknowledged that this was going to take some time to accomplish. The Four Families exhibit was intended to be something of a placeholder until full integration of the Berkeley history story could be accomplished.

Meanwhile, as Historical Society representatives described it, the Four Families exhibit would instead present a snapshot of the Black Berkeley story in the form of the story of four prominent and influential historical Black Berkeley families. Those four families were the Reids (my mother’s family), the Howards, the Rumfords, and the Griffins. Representatives of each of the four families were eventually contacted, brought into the process, and asked to provide photographs from their family collections, to create accompanying narratives for the photographs, and, where possible, provide family memorabilia-family Bibles, actual photographs and letters, etc.—for display.

The exhibit would be curated by the same local historians—Harvey Smith and African-American Dr. Stephanie Anne Johnson—who later organized the 2021 Historical Society Black Berkeley History event mentioned above. The Four Families exhibition operated from the end of October, 2019 until the COVID pandemic shutdown forced its closure in March of 2020, a month before its scheduled ending.

Harvey Smith and Dr. Stephanie Johnson, co-curators of the “African Americans in Berkeley’s History and Legacy” exhibit in 2021 and the "Four Families" exhibit. In the background is the Timeline of Berkeley History exhibit.

In a handout released shortly before the exhibit opening, the Historical Society described the Four Families exhibit as “the first in a series of exhibits to explore the extensive history of African Americans in Berkeley,” adding that “the exhibit will include a rich photographic record, personal memorabilia from several families, and special programs including film presentations.”

Unfortunately, rather than make up for the errors the Historical Society had made in the past in overlooking and misrepresenting Black Berkeley history, the Society’s Four Families exhibit introduced its own set of even worse misrepresentations.

As the participating representative from the Reid family, it was my job to produce the materials and put together the Reid story for our portion of the exhibit. Using the Timeline Of Berkeley History exhibit as my model—photographs with accompanying paragraphs of identification and narrative—I laid out the Reid family story in chronological order, from its roots in Georgia and Virginia through its stops in abolitionist Massachusetts and its travels by boat or across the Plains states by wagon and rail to end up first in Sacramento, then San Francisco, and eventual settlement in Berkeley.

Attention in the Reid narratives on our photo storyboard was paid to family members who had special stories or notable accomplishments.

There was the great-great-grandfather—William Henry Galt—who walked out of slavery in Virginia and who later became Captain Galt, the commander of an African-American militia in Sacramento in the chaotic years following the end of the Civil War.

Sacramento Zouave, of the militia commanded at times by Captain William Henry Galt.

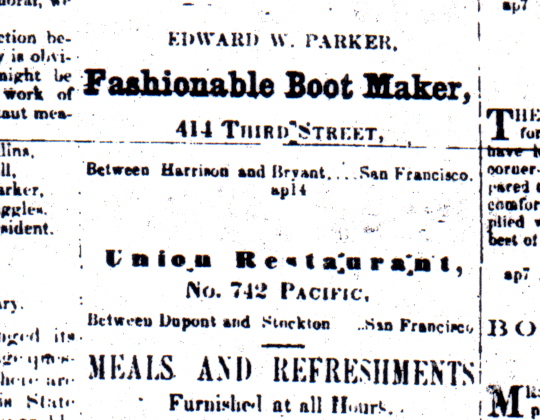

Or the other great-grandfather—Edward Parker Sr., also of Virginia—who was an officer in the most important African-American rights organization in the years just following the Civil War.

Notice in the San Francisco Elevator, African-American newspaper of the 19th century, advertising Edward W. Parker's San Francisco boot making business.

Or the grandfather—Thomas Reid Sr.—who escaped his hometown in Griffin, Georgia just ahead of a lynch mob.

Thomas Reid Sr. with nephew Mel Reid and daughter Alberta Reid, photo circa 1920 possibly taken at what later became the Berkeley Acquatic Park.

Or the cousin—William Patterson—who was one of the legal representatives of the Scottsboro Boys in their infamous Jim Crow-era rape trial, who later wrote the petition charging the United States with genocide against the African-American people that his friend, the great Paul Robeson, presented to the United Nations.

Or the uncle—Charlie Reid Sr.—who was a star pitcher in the Negro League feeder leagues in the Bay Area, later the mentor to hundreds of young East Bay athletes, several of whom eventually excelled in professional sports.

Charlie Reid mentoring youth in Richmond, CA.

Or the aunt—Florence Reid Lewis—who married the man who later became the light-heavyweight boxing champion of the world. John Henry and Florence ended up being the parents of the first woman—Tarika Lewis—to join the Black Panther Party, an accomplished jazz musician who once toured with John Handy.

Florence Reid Lewis sitting with nephew at her Berkeley home.

Or the aunt—Dorothy Reid Pete—who integrated the staff at the previously white-only Oakland YWCA in the days when much of Oakland was as segregated as the Deep South.

Dorothy Reid Pete.

These photos and depictions of members of Reid family in our presentation was preceded by a brief introduction to outline the Reid family story.

Shockingly, while the photos made it into the final exhibit as approved by curators, the introduction, or information on the individual family members whose pictures were being presented did not. All of information that family historians and members had gathered over the years about our family, all of the stories shared down through the generations so that our family history would not be forgotten, all of information from the scraps of letters faithfully saved and the long hours of research accomplished in libraries and public offices, from hard-to-see microfilm and microfiche and later, online, all of the written material on the Reid family submitted for the Historical Society’s Four Families exhibit so that visitors would know who the Reids were and where they came from and what they had done in their lives, all of that which was so invaluable to the Reid story, this was all arbitrarily proposed to be cut out by the exhibit curators.

Why? To be honest, more than a year later, while I know what the curators said, I’m still not sure about the actual reason behind the removal of the written Reid information from the main exhibit display.

Shortly before the Four Families exhibit was scheduled to open in late October, 2019, as Historical Society volunteers were still in the process of preparing the display panels, I got the following email from one of the curators. They had, the curator said, “a wonderful over abundance of text from you that is out of proportion to the other families. Would like to solve this dilemma by having your introduction in a binder on a podium next to your wall. Likewise for the captions. We will use shorter ones with the more detailed ones in a binder keyed to each photo.”

It took me a while to decipher what it was they were suggesting. When I finally figured it out, I immediately decided that this last-minute reorganization of the Reid materials was unacceptable, and I let the curators know that.

As I earlier said, the concept of the Reid family photo panel for the Four Families exhibit was based upon the Berkeley Historical Society’s Timeline Of Berkeley History that it had introduced at the Society’s 40th Anniversary celebration.

Berkeley Historical Society volunteers in front of the Society's Timeline of Berkeley History.

While there were things about the content of the Society’s Timeline that I didn’t like, I loved the way it was presented. It was set up on two large whiteboards, with photos and accompanying text. You could stand in front of them and in a few minutes get a good and grand picture of the sweep of Berkeley history. Similarly, the original Reid panel created for the Historical Society’s Four Families exhibit was designed so that one could stand in front of it and in a few moments take in the history of the Berkeley Reids unfolding before your eyes.

Putting the written portion of that history into a binder on the side would destroy that intended grand effect.

Most visitors to the exhibit would not bother to look at it, and for those who did, the effect would not be the integrated photo/text experience as had been intended. Instead, for most visitors, the Reid portion of the exhibit would consist of photos of anonymous, old-timey Black People who may have lived in Berkeley sometime, but were now long gone. It would have promoted the idea of a diverse Berkeley sometime in the past, which may have been the intent of the operators of the Berkeley Historical Society. But presenting those long-gone Black Folk without their names and stories attached would have been, intentionally or not, highly disrespectful to the very people the exhibit was supposed to uplift. I knew most of the people pictured in the Reid exhibit. They are my elders, a tribe of strong and fiercely independent people who came out of slavery and survived, excelled, and sometimes prospered in a West Coast environment that, officially at least, not especially welcoming to them. I would not have dared in real life to disrespect them by attempting to mute or distort their voices. I refused to disrespect them in that manner after these elders no longer had the earthly voices to respond themselves.

Although there were only a few days left before the exhibit opening when the binder-on-the-side decision was presented, I rejected the curators' “suggestion” and tried to come up with a better solution to whatever was bothering them about the Reid portion of the exhibit, a solution that might be acceptable to both sides.

I first suggested—reluctantly, I admit—that rather than accept the cutting out of the introduction and most of the captions from the Reid display, I would cut down some of the text myself or, in the alternative, eliminate some of the photos themselves if it was the saving of space that was necessary.

It was at that point the curators made me understand that it wasn’t the “over abundance of text,” as they had said in their email, that was the real problem, but the fact that the way the Reids had organized our exhibit was “out of proportion to the other families.” In other words, the Reid had extensive texts to accompany our photos, while the other three families did not.

I knew that the Rumfords, the Howards, and the Griffins—the other Black Berkeley families in the exhibit—all had family stories and family members as interesting as the Reids; they had simply not boiled those stories down to photo caption form. It was too late to do anything in time for the upcoming exhibit opening, which was then only a few days away. But I suggested to the curators that in order to eventually get the exhibit right, we put together a limited presentation for the opening, then close the exhibit immediately afterwards to give time for the other families to create narrative photo captions similar to what the Reids had presented. I offered my assistance as a writer and an editor to help the other families write those captions. I figured that working hard, we could accomplish all of that in no longer than two to three weeks, and a better version of the Four Families exhibit could re-open immediately after that.

Handout for the Berkeley Historical Society's Four Families exhibit

The curators rejected that suggestion without much explanation. As far as they were concerned, the Four Families exhibit would go on as they had re-organized it, with the Reid family members hanging mute on the photo board, their stories closed up in a binder somewhere across on the other side of the room.

Given no other choice than to submit to the way the curators had decided to present my family’s story, I pulled my support from the Four Families exhibit.

As one of the Reid family historians, I knew I have a continuing mandate to use the family archives I’ve been entrusted with maintaining to present the Reid story to both our family and to the general public. At the same time, I also believed I had no similar mandate to remove the Reid portion from the exhibit, and there was no time before the exhibit’s scheduled opening to contact family elders and create such a mandate. And in the interests of full disclosure, others of the Reid family who saw the changed exhibit were not nearly as upset and offended as I was, if at all. I respect their opinion, even where we’re in disagreement, and they, of course, can speak for themselves.

So I did not pull the Reid photos down from the presentation whiteboard on my way out the door, as I might have done in my old radical days, or make a public call for a boycott of the Four Families exhibit over the way our family story was being treated. I made the decision for myself, and not the family, to take the old civil rights-era path of non-cooperation, and simply walk out.

So what is to be done now?

This is an information piece. For my part, I believe that the Berkeley Historical Society must stop misrepresenting the history of Black People in Berkeley and use whatever means at their disposal to integrate our true story into the greater Berkeley history. Otherwise, that greater Berkeley history is not actually a true history, is it? I’ll continue to wait patiently, and watch carefully when I can, to see if they get it right, at last. But having passed on my story about our treatment at the hands of the Historical Society I now turn it over to you, putting it in your hands to decide how that correction ought to be accomplished. Watch with me or take other action, if you choose.

It’s now up to you.

The Reid elders at the 2004 Reid Family Reunion. l-r: Maybelle Reid Allen, Florence Reid Lewis, and Dorothy Reid Pete. All three passed away a year and a half later.