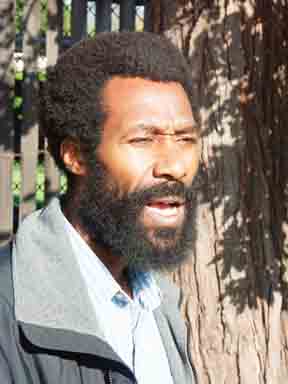

Patrick McCullough

WHEN POLICE BECOME ADVOCATES

Once a crime has been committed, we rely

upon the police to gather the evidence that leads to the arrest of a suspect, and

allows the district attorney to prosecute–and the courts to convict–the guilty party.

But we have also charged the police with another role–crime prevention. In some communities,

that means working closely with groups of citizens to monitor problem situations

and step in early to prevent them from escalating into crimes. That type of work

has sometimes been called "community policing," although it is one of those

easily-confusing terms that means different things to different people. In any event,

in Oakland that police-community crime prevention collaboration usually comes in

the form of the Neighborhood Crime Prevention Councils (NCPCs), which function as

neighborhood crime watch groups.

In this column, we have spoken in the past about one potential problem with calling

this NCPC-police collaboration "community policing." The people who participate

in these crime prevention councils do not represent the entire community, and so

sometimes what the NCPC people want the police to do is not necessarily what others

in the community want the police to do. This doesn't mean that the NCPC members are

bad people. Most of them, I suspect, are good, concerned, dedicated citizens who

take out time out of busy days and nights to try to make the community better for

all of us. But we always have to be careful in confusing the interests of the few

with the interests of the whole.

But there is another, more serious potential conflict between the crime prevention

role of the police in their NCPC collaboration, and the investigative role of the

police once a crime has been committed. What if the person accused of a crime is

a member of a crime prevention group with which the police have been working?

Of course, most of us know that the police often play favorites in law enforcement,

giving one person a break, coming down hard on another, taking sides based upon their

own prejudices and assumptions. The Oakland Police Department is currently operating

under federal court monitoring because of just such problems, and three former Oakland

police officers (commonly known by the name of the "Riders," a gang-like

title they gave to themselves) are on trial on charges of breaking the law to harass

people who they couldn't legally put in jail.

But when making public comments after a crime has been committed, police usually

try to make a show of objectivity to make us believe that they are being fair.

In the case of the recent North Oakland flatlands vigilante shooting, at least one

prominent Oakland police official is not even bothering to do that.

Patrick McCullough

In reading the Berkeley Daily Planet article on the shooting

by Matthew Artz and two San Francisco Chronicle articles by Jim Herron Zamora,

we can agree upon two sets of facts: First, 49 year old North Oakland homeowner Patrick

McCullough is a member of the North Central Oakland NCPC who has been active in recent

years trying to rid his 59th Street neighborhood of drug dealers. Second, on a Friday

night in mid-February, McCullough shot 16 year old Melvin McHenry in the arm while

McHenry was with a group of young men on the sidewalk in front of McCullough's home.

McHenry was not seriously injured.

After that, the stories of the perpetrator and the victim go in opposite directions

while describing the same chain of events.

According to the newspaper accounts, McCullough said that the group of youths taunted

him as he was walking out to his car, at least one of them calling him a "snitch"

because of his actions in calling the police on local drug dealers. McCullough then

said that some of the youths threw some objects at him, and he got in a scuffle with

one of them–McHenry. McCullough says that McHenry then went to one of his friends

to get a gun at which point, to protect himself, McCullough pulled his own weapon

and shot the youth in the arm.

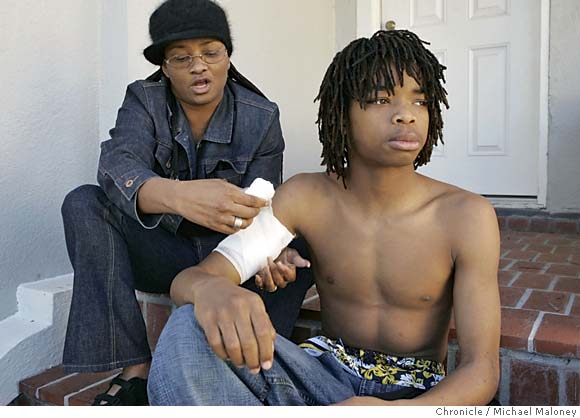

Melvin McHenry and His Mother

McHenry, who is a junior at Deer Valley High School in Antioch

and lives with his family a few doors away from McCullough, said that it was McCullough

who instigated the confrontation, yelling at the youths as he came out of his house.

McHenry says that he and his friends called McCullough a "snitch" in retaliation,

and that McCullough then came up to him and grabbed him. He said he punched McCullough,

and then McCullough pulled the gun and shot him as McHenry was trying to leave. McHenry

denies that he was trying to get a gun from one of the other youths.

Both McCullough and McHenry are African-American.

Both stories sound plausible and when you read it in the paper–without knowing the

individuals involved or all of the circumstances–you can't really tell which side

is correct. Sorting out the truth of it–and presenting the evidence to the District

Attorney's office–is the job of the police. To get at that truth, the police need

to approach their investigation with an objective eye.

But it's hard to find any objectivity in the statements of Lt. Lawrence Green, the

North Oakland watch commander and police liaison with the North Central NCPC.

"The reason that Patrick was assaulted by these suspects is that he stands up

to drug dealers in a way that normal citizens do not," Lt. Green was quoted

in one Chronicle article. In the second Chronicle article, Lt. Green

says, "In our opinion, [the 16 year old] was the aggressor–he instigated the

whole event." The "our" in this case presumably means both Lt. Green

and the officers under his command who are charged with investigating the case. And

the Planet article says that Green has gone even further, mobilizing North

Central NCPC members through an internet discussion group to pressure the District

Attorney's office not to prosecute McCullough. Green has told the Chronicle

that it is the younger McHenry who should be prosecuted.

Perhaps Lt. Green is right, and the 16 year old and his friends were the agressors

in the incident. But as a society, that is something we are supposed to decide in

an orderly process–in a criminal trial, where each side gets to present its facts,

and the police are called upon to testify as to what they have uncovered. When police

officials become impatient and decide that they need to interject themselves as public

advocates for one side or the other before the trial begins–before anyone has even

been charged–then the question necessarily arises: did the police have their minds

made up when they got the first call of a shooting on 59th Street and found out it

was one of their allies who was charged with a shooting? And if that is so, how can

any police investigation in this matter be trusted, or any evidence they present

be believed?

By going from investigator to public advocate, Lt. Green has crossed a line. The

rest of society is free to take sides in such disputes. The police department is

not.