![]()

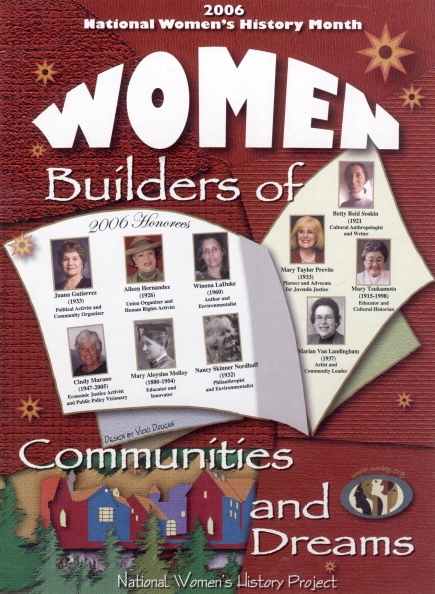

BETTY REID SOSKIN: RICHMOND COMMUNITY ACTIVIST EARNS NATIONAL HONOR

By Suzanne LaBarre

March 17, 2006

There have been many Betties.

There was Wartime Betty, Artist Betty, Political Betty, Black Nationalist Betty.

There was Married Betty, Divorced Betty, Mother Betty, Midlife Crisis Betty. There

was New Orleans Betty, Berkeley Betty, Dancing Betty, Painting Betty and lately,

Blogging Betty.

This month, the National Women‚s History Project will pay tribute to the woman who

has reinvented herself more times than Madonna: Richmond resident Betty Reid Soskin.

The project has highlighted women‚s historical achievements since 1980. Soskin and

nine other women will be honored in Los Angeles this Sunday, and again March 22 in

Washington D.C.

Soskin, 84, was selected for demonstrating the year‚s theme:

Builders of Communities and Dreams.

Soskin, 84, was selected for demonstrating the year‚s theme:

Builders of Communities and Dreams.

And build she has.

As a South Berkeley shop owner, she helped overhaul a drug- and crime-infested neighborhood,

earning her the 1995 honor California Woman of the Year. In more recent years, she

has worked to shore up Richmond‚s historical record, by resurrecting the stories

of residents in war-era black neighborhoods.

Her investment in military history is deeply personal.

As a young woman during World War II, Soskin took a job clerking for the Boilermakers

A-36. Like many women of the time, she was dubbed a „Rosieš for contributing to the

wartime effort, though she did not consider herself one, she said. She pointed out

that African Americans did not join the workforce until later in the war, and the

term „Rosieš largely referred to white women.

After the war, Soskin settled down to raise a family in Walnut Creek, a time in her

life she branded her „lowest and highest point.š

The sleepy East Bay suburb, then a stronghold of white ultra-conservatives, was loath

to welcome a black family into the community.

„I became the target of racial hatred, by virtue of being the first [African American]

family on the block and the second family in that valley,š she said. „The white community

we moved into thought one of their rights was their denial of mine.š

To steel herself against discrimination, Soskin became active in the local Unitarian-Universalist

community. But it only took her so far.

As the pressure of her oppressive environs mounted, Soskin‚s marriage started to

crumble and her eldest child spiraled deep into a troubled adolescence.

„I just caved in,š she said.

Unable to resume day-to-day functioning, Soskin palliated her midlife crisis with

Jungian therapy. Therein she discovered myriad new Betties.

„I began to write music and to sing and to paint,š she said. „Things just seemed

to move out of my subconscious into my conscious state. I was a whole, totally reinvented

Betty, who was an artist.š

Then, like that, she reinvented herself yet again.

„I became political Betty,š she said.

After her first husband fell ill, Soskin ventured to Berkeley to save his business,

Reid‚s Music Store on Sacramento Street at Prince Street. The area was a veritable

wasteland of drugs and prostitution. Soskin quickly realized that the only way for

the store to survive was to overhaul the neighborhood.

Thus began an estimated $8.5 million, seven-year battle to

replace a two-block crime-ridden expanse with 41 units of low-income housing.

Thus began an estimated $8.5 million, seven-year battle to

replace a two-block crime-ridden expanse with 41 units of low-income housing.

It was a grueling process, she said, that contributed to the downfall of her second

marriage.

But it also reaffirmed her identification with the black community.

„It was a period that was really rich,š she said. „I really came to terms with the

fact that my salvation lay in my racial identification, and that‚s when my Africaness

came to the front, and that‚s what I move out of.š

For her triumph over the South Berkeley slum, the California State Legislature nominated

Soskin Woman of the Year in 1995. Soskin went on to work as a field representative

championing the causes of two California state assemblymembers, Dion Aroner and Loni

Hancock.

In the late 1990s, Soskin became involved in the Black Power movement, pushing for

the recognition of the black agenda in the Unitarian-Universalist Association.

More recently, Soskin has taken on a major role developing the Rosie the Riveter/

World War II Homefront National Historical Park, an auto tour in Richmond.

Though the city is a goldmine of World War II-era relics, the historical ledger often

excluded African Americans.

Soskin worked to change that.

Thanks to her efforts, the park acknowledges the role of black neighborhoods surrounding

the site of mass industrial production during World War II. The neighborhoods were

bulldozed following the close of the war.

While digging up these accounts, Soskin has turned to recording her own history.

She has been a prolific blogger since 2003, turning out several entries a week. Entries

range from detailing the care of her disabled daughter, to describing obscure local

stories, generously peppered with outrage over the paucity of historical awareness

in Richmond.

But her blog serves a more personal purpose, too, she said. It is for her children

and family so they may learn about the woman who has been many different women, and

the woman who doesn‚t plan to stop reinventing herself now.

Soskin‚s blog can be found at http://cbreaux.blogspot.com/.