African Captive Cook÷Refuge Plantation, Camden County, Georgia

(Photograph by L.D. Andrew, 1936, from a vintage photograph taken ca. 1880)

A BRIEF HISTORY OF

THE GALTS, TURNERS, AND PATTERSONS

Excerpted from

"THE MAN WHO CRIED GENOCIDE"

by William L. Patterson

[Note: William

L. Patterson was the grandson of William Galt and Elizabeth Mary Turner, who migrated

from Virginia to California during the Civil War. Patterson was a writer and organizer

who, during the 1930's, became one of the top African-American officials in the Communist

Party of the United States. He was the author of the famous "We Cry Genocide"

petition that Paul Robeson presented to the United Nations in protest of the American

treatment of African-Americans. Patterson was a world-renowned scholar and historian

but he apparently relied heavily upon his mother's account of the family's years

in Virginia and the trek to California,and there are possibly small discrepancies

in the account.]

My mother often talked to

us about her childhood on the Virginia plantation where she was born as a slave in

1850 and had lived until she was ten. It was in cotton lands not far from Norfolk÷she

knew that because her grandfather, who often drove to the "big city," was

seldom gone for long. Her father, William Galt, was a slave who belonged to the owner

of an adjacent plantation, and as a child she saw very little of him. As coachman

for the master--who was also his father÷he drove back and forth on visits to the

Turner plantation, where he met and later married my grandmother, Elizabeth Mary

Turner.

The big house was set back from the magnolia-lined plantation road leading to the

main highway to Norfolk. But my mother lived in the slave quarters, which were quite

some distance back from the manor house. Here, separated from her mother and grandmother,

she lived with older slave women who were part of the crew that served the master's

immediate household.

My grandmother was personal maid to the white wife of her father and master; my great-grandmother

was head of the house slaves and also her owner's slave woman (at that time the word

"mistress" was not used in that sense). My mother had learned of her grandmother's

role from gossip among the field hands, but it was beyond her to question the morality

of this situation. Morality played no part in the relationships between white slaveowners

and their slave-women--the masters' morals were class morals in judging the slave

system or their own personal relations with slaves.

According to the gossip, my great-grandmother first came to the notice of the big

house through her ability as a cook. In line with the general mistreatment of field

hands--rags for clothing, shacks for living quarters, cheap and primitive medication--they

were never well fed. When my mother's grandmother was living among the field slaves,

she got the slaves who slaughtered and cut up the hogs and cattle to bring her the

entrails, hooves, heads and other "throwaway" parts, along with similar

leftovers from chicken killings. Somehow she had acquired great skill in the use

of herbs for cooking as well as for healing. She converted the leftovers into such

tasty dishes that she soon gained a reputation as the best cook on the plantation.

Before long she was ordered into the big house to cook for the master's family. She

was an attractive woman and, as the story goes, the master found more than her cooking

to his taste. Eventually she gave birth to three of his children.

African Captive Cook÷Refuge Plantation, Camden County, Georgia

(Photograph by L.D. Andrew, 1936, from a vintage photograph taken ca. 1880)

Field hands, according to my mother, said that Cap'n Turner's wife

knew of the relationship÷it would be something in the nature of a miracle had she

not known. But there was little or nothing she could do about it and, after all,

the slave mother and her children were no economic threat to her.

Despite his slaveowner's morality, great-grandfather Turner revealed a sense of responsibility

toward his families÷both Black and white. He recognized the danger of war to his

children, as did his friend Galt, and he believed in the right of a master to free

his slaves. Before the war broke out, he managed to move his families away from the

land that was destined to be drenched in blood. He sent his white family north to

Bridgeport, Connecticut, the Black family west to California. My grandfather Galt

sent his son along with them.

My great-grandmother, then an old woman, stayed behind with the father of her children÷they

must have been deeply attached to one another. My grandmother was given the responsibility

of settling her white relatives in New England. The trust reposed in her was not

an uncommon thing. Her master obviously had great faith in his dark-skinned daughter's

ability to take care of duties like these.

Those who were sent on the Westward trek went by way of Panama and from there across

the Isthmus. The trip down the Atlantic Coast may have been more or less routine

but crossing the Isthmus along a narrow, single-track line must have been more difficult.

At Colon on the Pacific side, the freed men and women took a ship to San Francisco÷a

long and hazardous trip.

It is likely that the Black Galts and Turners were sent to California by way of Panama

to avoid the overland trek through Indian territory as well as to escape the fugitive

slave hunters who plied their lucrative trade beyond the Eastern seaboard.

My mother, Mary Galt, was about five-feet-three in height. Her complexion was brownish

yellow; her hair wavy, with streaks of gray as she grew older. Strong and energetic,

she was a fighter when she knew what the fight was about. She was ten when her grandfather

sent his liberated Black children west.

Mary Galt Patterson (Eliza)

Known among the Reid children as Auntie Pat

William Patterson's mother

Originally there were four children in our immediate family. My

sister Alberta was the child of my mother's marriage to Charles Postles, who came

west from North Carolina. He died shortly after Alberta was born, and my mother subsequently

married James Edward Patterson

A few years after he arrived in California, grandfather Galt organized a regiment

of Negro volunteers known as the California Zouaves. Undoubtedly my grandfather feared

the efforts of confederate sympathizers to take California, a free state, out of

the Union and was determined to do anything to help prevent such a monstrous catastrophe.

Governor Frederick P. Low of California honored him for his work in his regiment

at a banquet in Sacramento, the capital, presenting him with a huge pewter platter

and pitcher on which were inscribed the names of the governor and my grandfather.

The set fell to our branch of the family and remained a cherished heirloom until

we were forced to pawn it.

William Galt took part in other great liberation battles, prepared anti-racist conferences and conventions, helped fight civil rights cases through the state and federal courts in valiant efforts to make the Emancipation Proclamation and post-Civil War constitutional amendments instruments for freedom.

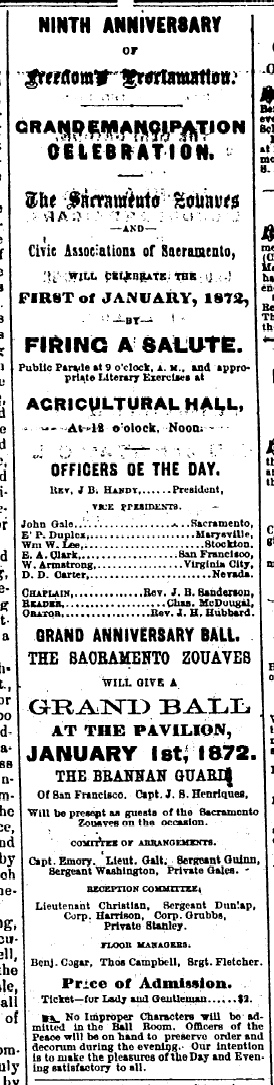

Emancipation Day Celebration sponsored by the Sacramento Zouaves, January 1, 1872. Such celebrations were common among AfricanAmericans around the country during the years when people still had a living memory of slavery and the Civil War, continuing in the Southölargely through the churchesöuntil late in the 20th century. Advertisement is from the December 29, 1871 Edition of The Elevator newspaper, A Weekly Journal of Progress, the colored newspaper of San Francisco, California. William Henry Galt is noted as Lieut. Galt under the COMMITTEE OF ARRANGEMENTS near the bottom of the notice.