The Desegregation of the Oakland Fire Department

Sarah Wheelock

University of California at Berkeley BA History Project

How great a matter a little fire kindleth. ŲJames 3:5

Few people feel that they have the best job on earth. And fewer still work among

a group of people who almost unanimously feel that they have the best job on earth.

For firefighters, this belief is normal. A firefighter for the city of Oakland noted,

„They believe that∑there is nothing else but this, that you could not want a better

job. This is the best job.š

Another Oakland firefighter, remembering a friend who went to work

for the department several years before him, found it hard to believe that the friend

never adequately expressed how much the job meant to him: „I said to him, őHey, how

come you never told me about this long ago?‚ He said, őIf I would‚ve told you, you

wouldn‚t have believed it.‚š

A sense of duty, of doing an important job, of a responsibility

to the community are all part of what it means to be a firefighter. The feelings

of responsibility and duty extend to coworkers as well. Fire fighting has a close-knit,

proud culture often called a brotherhood and an extended family. Firefighters are

not simply co-workers, they spend days and nights in each others‚ company, living

and working together in shifts that are usually at least twenty-four hours long.

Group harmony is extremely important, both for mundane reasons of the pressures of

living together and the vital reasons of working effectively as a team in a life-threatening

environment. As a researcher of the modern Oakland Fire Department states, „The cultural

significance of the twenty-four hour shift cannot be overstated: this schedule means

that the firefighters literally live together. The fire station becomes a combination

work-and-home environment, and coworkers constitute a second family, in some cases

rivaling or even replacing a firefighter‚s non-work relationships.š In a recruitment

pamphlet from 1957, the Oakland Fire Department stressed the necessity of getting

along: „Since firemen must live and work together, personal qualifications

are extremely important. Great pains are taken in the personal interview to insure

among other things that the candidate has the kind of personal qualifications which

will enable him to live and work in harmony with his fellow employees.š Once accepted

into the community, many firefighters feel that they have a network of people whom

they can rely on. But what happens when this promise of brotherhood is not fulfilled?

While this solidarity and particular attention to interpersonal

relationships has its obvious benefits, these principles were in the early twentieth

century the justification for fire departments excluding men of color. For blacks

and whites to work together as firefighters was unthinkable, a form of integration

so radical as to be almost inconceivable. Not only would they be fighting fires together,

they would also be sitting down to the same table for dinner. If departments had black firefighters at all, they

served in separate, segregated fire houses where they had little contact with the

other members of the department and no chance for promotion.

Three Oakland firemen seated in wooden chairs facing

camera. Oakland's first black firemen were hired in 1920 and worked at a segregated

firehouse at 8th and Alice Streets, which later moved to 34th and Magnolia streets.

Integration of the fire department gradually began during the 1950's. [Photo courtesy

the African American Museum And Library At Oakland (AAMLO)]

From approximately 1926 to 1955, the Oakland Fire Department employed

African American firefighters in a separate fire station in West Oakland. The station

had its own rigs, and responded to fires in exactly the same manner as all the other

fire stations in the city. Fire did not discriminate, but the department did not

want to have the black firefighters of Oakland in too close contact with their white

counterparts. The black firefighters of the Oakland Fire Department began a full-fledged

attack on the segregated department in 1952. Through a variety of means and with

the assistance of the NAACP, the black firefighters attempted to desegregate the

department. But no matter how desired desegregation was by the firefighters, the

black public, and the rest of the city government, change could ultimately only come

by way of the Fire Chief.

The Men Of Engine 22

Engine Company 22, also called Station 22 or 22 Engine, was an

all-African American fire fighting company in the Oakland Fire Department. Founded

around 1920, Station 22 was until 1955 the only station in Oakland that black fire

fighters could work. Entrance into the prestigious job was difficult. Although the

city of Oakland at least 30 fire stations, any black man wishing to work for the

department had to wait until an opening appeared in Station 22, which could take

years. In addition, appointment to any civil service job was difficult and often

depended personal connections. The process for obtaining a civil service job started

with a written exam, which when passed was followed by an interview with a panel.

For many African Americans, the hiring process ended at this point. Lionel Wilson,

who was an attorney for the NAACP in the 1950‚s and later became mayor of Oakland,

tried to get a civil service job after he graduated from U.C. Berkeley:

The post office exam I took myself, and the first time I think

I was fifty-two on the list or something like that. The way I found that they had

passed me up was when I ran into someone who was lower on the list--120, 150, or

two hundredųwho had been working for about six months. And that was the way I learned

that they had passed me up on the list.

Then one of my brothersųhe‚s now a dentistųhe had taken it, and

he was 120 on the list. At that time the federal government didn't ask for race,

but they asked for a picture. I was the darkest in the family. Well, when they looked

at my brother, they thought he was white, so they offered him the job when they got

down to him.

Lionel Wilson

Then I took it again, and this time I was fifth out of thirty-five

hundred, I just had a couple of people ahead of me who had veterans' preference.

I was called in for an interview, if you want to call it that, this time. But it

didn't really amount to anything other than to be told by the assistant superintendent

of mails that, „The fact that you're called doesn't mean that you are going to get

the job,š as I well knew. And I didn't.

The probation department here, which, at that time, had no Negroes

in itųI took that exam, and in that exam you were not called for an oral unless you

passed the written. So when I was called in for the oral it meant that I'd passed

the written, and about the only questions they asked me was, „You're Lionel Wilson,

you graduated from the University of California, Berkeleyš „Yes, that's right.š „Why'd

you take the exam?š I told them. They said, „Fine. You'll hear from us in a couple

of weeks.š Well, I did, that I'd failed to pass the examination.

Tarea Hall Pittman, former general secretary of the Berkeley NAACP,

noted that civil service jobs in the 1950s were notorious for refusing to hire black

people. She explained the process by which the NAACP went about trying to open these

jobs to African Americans:

We would receive complaints...We would then go to the Civil Service

Commission of the City or County and try to find out why these particular Negroes

didn‚t pass or why they couldn‚t get placed on the list to be appointed. We got all

the factual data. Then after we had the factual data or got individual complaints

from people who had been discriminated against, we would go to the Board of Education,

to the City Manager or the City Council or the County Board of Supervisors, or whoever

was in charge of that particular institution and try to find out why this discrimination

existed and what could be done about it and try to exert enough pressure on them

to get them to lift their discriminatory practice from the facility.

In the case of the Oakland Fire Department, matters were slightly different.

Because a segregated station existed, black men were allowed into the department

in a limited capacity. However, jobs were only available in the station when someone

left or retired, so getting a job was difficult. In addition, favoritism and backroom

deals made the prospect of getting a job in the Oakland Fire Department a tricky

situation.

Royal Towns

[Photo courtesy the African American Museum And

Library At Oakland (AAMLO)]

Royal Towns, born in Oakland in 1899, began working at Station

22 in 1927. Denied union membership in his factory job because of his race, in 1921

Towns went to work on the railroads, a common occupation among black men in the East

Bay. He applied for a job with the Oakland Fire Department while working as a porter

on the Southern Pacific Railroad. Like many of the firefighters at Station 22, he

first heard of the job by word of mouth:

Well, how I got my job at the Fire Department was another story.

I was working on the Sunset Limited, running between San Francisco and New Orleans,

and I was on there one day, and I saw a fella, George Allen. And George was a fireman.

I said, „Hello George, how are you?š

„Fine,' he says, 'well, what are you doing, Royal?š

I says, „I‚m working on the railroad.š

He says, „Why don‚t you take the fire department examination? It

pays $200 a month.š

„Ooh, that sounds pretty good.š∑And I say „Gee, George, I don‚t

think I‚m smart enough for this.š

„Well come on, we‚ll train you for it.š

So I went with them and I started training.

Towns trained at Station 22 to pass the examinations. In spite

of his modesty about his intellect, it was not difficult for him. Growing up in multicultural

West Oakland of the early 1900‚s, he spoke at least three languages. Even so, he

did not get the job with the fire department until the morning he happened to be

serving breakfast to his former employer. As he remembered:

[His former employer] says, „Well, what are you doing on here?š

I said, „Well, they found out I was black.š So I said, „I had a

hard time getting in the unions and things like thatš

And he said, „Is this the best you could get?š

I said, „No.‚ I says, „I took the post office examination, the

police department examination, and the fire department examination.š

He says, „Which one do you want?š

I says, őI would like to have the fire department job.š

„Well,š he says, „you come and see me tomorrow up at the Niles

Athenian Club.š

So I went down to the Niles Athenian Club, went in there to see

Mr. Gross. „Well, Mr. Gross, here I am.š

He says, „Well, wait a minute, I‚m going to call the head of the

Public Health and Safety over there.š And so we called őem up. Frank Corbett was

the man in charge. And Mr. Gross says, „Hello, Frank?∑I‚ve got a very good friend

of mine. Used to work for me. And he‚s got a family and everything and he‚s taking

a job at the fire department. I‚d like to know when he‚s going to get appointed∑.

Oh,š he says, „on February the 14th, huh? All right,š he says, „now you take care

of him. That‚s my boy!š

So that was the end of that. So I got my job at the Fire Department.

Black firefighters, who obviously understood the difficulty of

getting a job in the department, conducted classes on passing the written test at

Station 22. Royal Towns, remembering the help he had received, helped many firefighters

to get into the fire department. He was the scoutmaster for a Boy Scout troop that

included Sam Golden, a boy who would grow up to be the first black chief of the Oakland

Department. In Towns‚ case, he had no strings to pull in the department, but he could

instruct potential firefighters and others looking for civil service jobs how to

pass the tests. C.L. Dellums, labor leader and NAACP activist, remembered Towns‚

efforts to help other people join the fire department, as well as his feelings about

the segregation of the station:

Roy was widely known, an able man, and he coached other young people

to help them pass the examination, not only for the Fire Department but for the Police

Department. He coached many Caucasians to help them get by, because he grew up, went

to school and lived in North Oakland, and had many white friends. Of course Negroes

were a minority in all schools there in those days and so the majority of his schoolmates

were white. Therefore there were plenty of them that went to Roy when they learned

that he was a fireman and an able and intelligent fellow. Of course, he helped quite

a number of Negroes to pass the examinations in those days to become a fireman.

Labor Leader C.L. Dellums

African American firefighters of the early half of the twentieth

century were considered an elite group of the black population of the East Bay. In

a time when employment opportunities were severely restricted for black men, fire

fighting was an honorable, middle-class profession. As a measure of the status of

firefighters, it is estimated that about half of the members of Engine Company 22

were members of the Prince Hall Masons , an exclusive black fraternal organization

that traces its roots in the United States back to 1775. Royal Towns, for example,

was the editor of the Prince Hall Masonic Digest. Prince Hall Masonry also

involved a number of prominent African Americans in the NAACP, such as C.L. Dellums,

who was in the same lodge as many of the Oakland firefighters. The NAACP and the

men of Engine 22 had many connections. Many of the men in Station 22 had worked for

the railroad and belonged to the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, of which Dellums

had been president. These connections helped the African American community to deal

with the persistent racism of the time. Dellums recalled another situation that illustrated

the close connections between the members of the black middle class of the Bay Area:

Florence [Crawford] was active in the Eastern Star. And I, an active

Shriner, and her husband, and active Mason and a Negro fireman [Price Crawford, one

of the first black men hired by the Oakland Fire Department] had been good friends

for years. Florence had taken the civil service examination and the type of stenographer

that was needed was very scarce. As she told me herself, they called her when she

passed the examination and on the strength of the papers wanted to know if she could

come to work right away. She finally agreed to go for an interview. The vacancy was

in the [then State Attorney General Earl Warren‚s] office in San Francisco.

Then when they saw she was a Negro, they began making excuses.

They said they had to interview a lot of other people and that they‚d let her know.

It was one of those „Don‚t call me, I‚ll call you,š deals. They didn‚t call her.

Finally her husband pleaded with her to „come see C.L. Dellums and try to get him

to help you.š

At first she was reluctant to do it. One reason was because Warren

was a Republican and I was a known Democrat. But finally she began to believe that

she was not going to get the position. She finally came to see me and asked me if

I would write Attorney General Warren a letter for her, and try to get him to put

her on. So I kidded her about it, „I‚m a Democrat, I don‚t think he‚ll even listen

to me. We‚ve always been on opposite side of political issues.

But she said she had reason to believe that a letter from me would

be helpful just the same. So I wrote the letter. About two days later she went to

work. Now whether the letter had anything to do with it or not, who knows? But about

two days after I wrote the attorney general about it, Florence went to work.

These sorts of connections between the men of 22 Engine and the NAACP would later

become vital in the struggle to desegregate the department.

In August of 1952, the article „Fire Chief Orders End to Segregation

in Departmentš suddenly appeared in the Oakland Tribune. Oakland Fire Chief

James Burke, according to the article, had agreed to „assign Negro firemen to vacancies

as they occur throughout the city.š Segregation in the Oakland Fire Department was

over. Or was it? At the same time Burke agreed to desegregate the station, he issued

the statement, „We had hoped by grouping these men to develop an esprit de corps

and pride in their company. This has not developed, but the men appeared to be satisfied

and there were no complaints of ősegregation‚ until recently∑there were no complaints

until about a month ago. Then agitators got busy and demands were received, mostly

from outside of the department.š

These „agitatorsš were the NAACP. According to Tarea Hall Pittman,

the NAACP had been involved with the Oakland black firefighters since the station

had been opened. Beginning in the 1950s, integration of the department became a goal

of the firefighters in Engine Company 22. In August 1952, 24 of the 27 black men

working for the department requested to be transferred to white stations. Although

Chief Burke had said that black firefighters would be transferred as spots opened

up, none of the 24 transfer requests were granted.

The whole situation was confusing. Was the department going to

be desegregated or not? After the transfer requests were ignored, the NAACP publicly

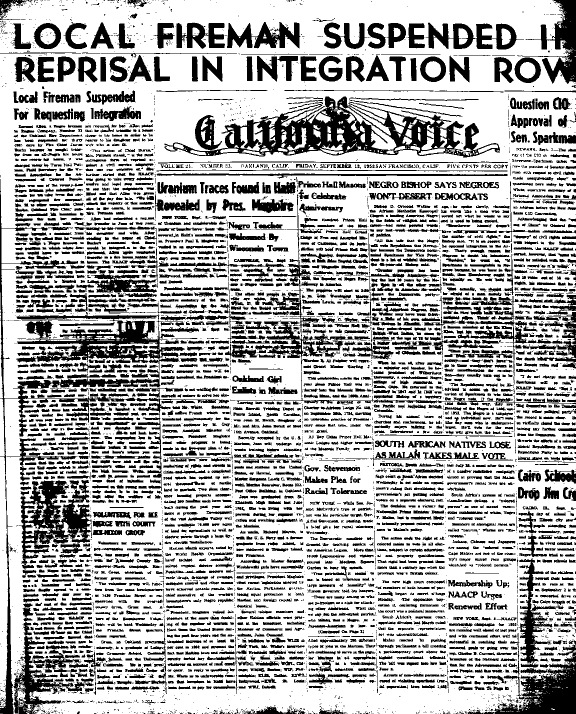

charged Chief Burke with bad faith. The major black newspaper of the East Bay, California

Voice, was following the proceedings closely. An article at the end of August

stated, „Even though Fire Chief James H. Burke had issued a statement to the press

that the Fire Department would be integrated, he stated to the [NAACP labor and industry]

committee in the presence of the city manager that he was personally opposed to integration

and felt it would not work in Oakland, without causing trouble∑The Association charged

him with bad faith in that he was attempting to mislead the public by giving a statement

to the press that the Fire Department would end segregation and yet he told the committee

that he would not say when the program of integration would be carried out or where

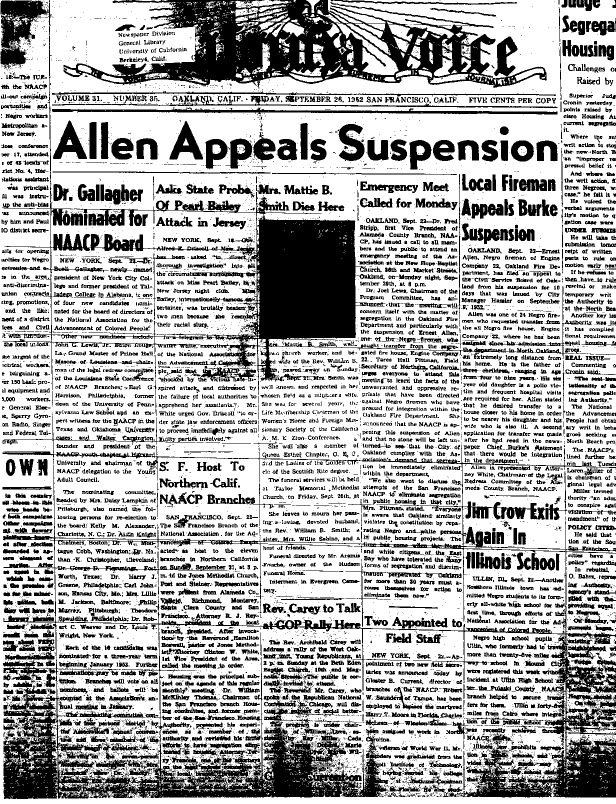

he planned to start.š One firefighter, Ernest Allen, had compelling humanitarian

reasons to be transferred to another station. The father of three children, his wife

was ill and one of his daughters had polio, requiring frequent trips to the hospital.

Hoseman Allen hoped to be transferred to a station closer to his house. After the

en masse transfer requests were denied, Allen resubmitted his application

for transfer, this time in person. A heated argument ensued with the battalion chief

in charge of personnel and according to Allen, Battalion Chief Harris dismissed his

application with, „It is not the policy of the department to transfer you colored

fellows to other stations.š

Indeed, it was not the policy of the department to transfer black

firefighters to other stations. It was never disputed that Battalion Chief Harris

was correct in his assessment of the department. Hoseman Allen brought a written

complaint to Chief Burke alleging that Battalion Chief Harris had told him that black

firefighters would not be transferred to other stations. Allen was suspended for

ten days, at the recommendation of Chief Burke, by City Manager John Hassler for

violating Rule 229 of the department, which states:

No member of the department shall wantonly or maliciously make

any false report of any other member either as to any offense or as to the business

of the department calculated to create disturbance or to bring any member of the

department into discredit.

Battalion Chief Harris denied that he had told Allen that black

firefighters could not be transferred to other stations. He alleged that Allen had

made up the statement to make him look bad, which allowed Rule 229 to come into use.

In reality, the application of the rule was a bit bizarre. Whether or not Harris

had made the statement, it was the policy of the department and to suspend Allen

for it was suspicious. To Allen and the NAACP, this suspension was punishment for

pushing for a transfer. Ironically, this heavy-handed use of the rule to punish Allen

for speaking up caused a greater disturbance for the department, earning it mention

in the San Francisco Chronicle, which had never thought it necessary to discuss

Oakland‚s black firefighters before. The department had committed a colossal blunder.

The NAACP had been involved with the firefighters of Station 22 for years, but never

until Allen‚s suspension did they have such a ready-made opportunity drop into their

laps. Who could defend the suspension of a hard-working fireman who, after all, simply

wanted to care for his family? „And you thought Hitler was dead∑š wrote Louie Campbell

on the front page of the California Voice. Allen immediately appealed the

suspension, and the NAACP stepped into high gear. C.L. Dellums called the suspension

an „administrative lynchingš and „an attempt at intimidation of the Negro firemen

in the department.š The black public responded to the crisis. People flooded a public

meeting held by the NAACP at New Hope Baptist Church in Oakland, eager to hear about

Allen‚s case and his upcoming hearing in front of the civil service board. J. Norman

Porter, comparing the struggles of the NAACP and Allen to the biblical hardships

of Job, recalled the meeting in an opinion piece for the California Voice:

„It was gratifying indeed to see the large group of intelligent citizens assembled

in the church as our dynamic leader of the NAACP, amiable Mrs. Pittman called the

meeting to order∑Space will not permit me to make casual commentation of this well-attended

meeting, but let me urge ALL to make definite plans to be present October 7, in the

Civil Service Commission Room of the City Hall in Oakland.š

The fire department could not suspend Allen directly. Instead,

Chief Burke had to recommend to the City Manager that Allen be suspended. The City

Manager was the member of the city government actually responsible for the suspension.

Allen had recourse to appeal the suspension in front of the Civil Service Board,

a three-person panel. After several reschedulings of the hearing, testimony was finally

heard on November 5, 1952. It was at this moment that it became fully public that

the fire department was segregated. Testifying on behalf of Battalion Chief Harris

and the Oakland Fire Department, First Assistant Chief Carl Weber was asked by Board

Chairman J. Clayton Orr if Weber would have any „hesitancy in telling a Negro he

couldn‚t be transferred to a white house because segregation was the reason.š Weber

replied, „No.š The not-so-secret rule was out in the open. Black firefighters were

not being transferred to other stations, regardless of what the Chief had said.

However, the issue, as far as the department was concerned, was Allen‚s violation

of Rule 229. As for Allen, Battalion Chief Harris said that the health of his child

was „insufficient groundsš for transfer. City Attorney Daniel MacNamara tried to

convince the board that Allen was asking for a transfer simply to discredit Battalion

Chief Harris, not so that he could care for his family. Allen, for his part, spoke

of his disillusionment of traveling around the country with his college athletic

team only „to come back to my home town of Oakland to encounter segregation.š When

asked, he said he still wanted the transfer.

A long fourteen days later, the Civil Service Board returned its

verdict: Allen‚s suspension was upheld, two to one. Clinton White, attorney for the

NAACP, stated, „This policy of segregation places a stigma on Oakland it can ill

afford to bear. As the chosen representatives of the people, the council should have

the opportunity to reverse this policy and issue directions to effect a policy of

integration. I cannot see how the council can condone a policy of racial segregation.š

The majority opinion of the Civil Service Commission focused solely on the violation

of department procedure, ignoring the larger issue of segregation in the department.

As the opinion states, „We believe the statements imputed to Chief Harris by Hoseman

Allen in his written report dated August 26, 1952, were not made by Chief Harris

and that Hoseman Allen‚s report was therefore false∑If Hoseman Allen felt that he

was being discriminated against, there were other avenues available to him to obtain

a hearing of his complaints. The Fire Department is a quasi-military organization

and departmental discipline requires that rules should not be violated in a procedure

of this kind.š

Chairman Orr disagreed with the other two members of the board.

„If, as was admitted by Chief Harris∑the established policy of the Fire Department

would deny the fireman the right to transfer because of his color, how can it be

said that the statement damaged or discredited Chief Harris‚ reputation, or that

of the Department, or that it was made wantonly or maliciously?š However, he was

in the minority. And contrary to Clinton White‚s assertion that the board could command

the department to desegregate, Orr went on to note that „this Commission has no jurisdiction

as to whether the Fire Department may or may not enforce a policy of segregation

in the operation of its fire houses.š Allen would not find help with the Civil Service

Board. He told the Oakland Tribune that he although he felt „pretty poorš

about the proceedings, he was impressed with Chairman Orr‚s opinion. Allen‚s case

was over. Whatever use it could have been to pry open the department was lost. The

NAACP and the black firefighters would need to pursue other options to integrate

the department.

It became rather clear that Chief Burke was adamantly opposed to

integrating the department, no matter his earlier statements to the contrary. Lionel

Wilson, an attorney for the NAACP who was later to become the mayor of Oakland, remembers

a meeting with Chief Burke, City Manager John Hassler, and Mayor Clifford Rishell:

We put up our arguments, and they sit there. An interesting thing

is that the mayor blacks out; I never remember who the mayor is. But the city manager,

I remember, was Jack Hassler, and the fire chief, [James] Burke.

When we finished, the fire chief was the only one who responded.

He spoke up and said, „If I were in your place, I would be saying the same things

you‚re saying. And it would make sense. But as long as I‚m fire chief, there will

be no integrated fire department in this city.š

James Burke joined the Oakland Fire Department at a time when most

fire engines were still being pulled by horses. He was no stranger to hardship. Born

in 1887, he was orphaned at seven when both of his parents died. He had no family

to take care of him and was placed in an orphanage. Joining the Navy at age 14, he

returned to the Bay Area after serving for six years, attending Sacred Heart College

in San Francisco. Burke studied at Sacred Heart for two years before the college

was destroyed in the 1906 earthquake and fire. He gave up school and worked for a

tea company for six years before joining the Oakland Fire Department in 1912. He

rose rapidly in the department, making lieutenant just five years later. He was promoted

to captain in 1921 and almost immediately to battalion chief in 1922. Ten years later

he became assistant chief, and in 1947 he became chief of the department.

He had ambitious plans for the department. In December 1947 he

went before the city council and informed them that the department needed new equipment

and facilities urgently. By 1950 the department had been radically changed due to

his efforts: 22 new pieces of fire fighting equipment had been purchased and 10 new

fire companies had been organized. The old drill tower, out of use since the 1920‚s,

had been replaced with a new, up-to-date version. A tugboat had been purchased from

the Navy and converted into a fireboat, Oakland‚s first. In 1951 the department was

upgraded from a Class 4 rating to a Class 3 by the National Board of Fire Underwriters,

a point of pride for the department also resulting in lower rates for fire insurance

in the city. According to one battalion chief in 1950, Burke always had the interests

of his men in mind. „When he took over, he told me that anything I did in the department

mustųand he emphasized thatųbe for the good of the men. And that‚s the way it‚s been.š

Perhaps he believed that integrating the department would cause hardship among the

men, or cause the department to be thrown into chaos. Lionel Wilson did not believe

so. When asked about the Chief, „how could he see your point of view and still refuse

to make some changes?š Wilson replied, „Because he felt that there was a place for

blacks, and that was it, and it was not in an integrated society.š

The NAACP needed to look at other options. Oakland had a city manager,

mayor and city council form of government. The city manager had shown his support

of Chief Burke‚s policy by supporting Allen‚s suspension. The next move would be

to petition the city council. While Hoseman Allen‚s drama was playing out with the

fire department, the civil service board and the city manager, the city council appeared

to be oblivious to the implications of the matter. Instead, they were busy with a

drawn-out investigation of Fairyland, a children‚s theme park. However, it hardly

mattered what the city council thought. In February of 1953, after Allen‚s suspension

was upheld, the council resolved that there would be a „policy of non-segregation

in all departments of city government.š This was followed two weeks later by the

self-congratulatory note to the meeting of February 19th, „Communication from National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People thanking City Council for passing

recent resolution expressing policy of non-segregation in all departments of city

government was read and placed on file.š Again, even though this appears to be a

move toward the desegregation of the department, nothing came of it. These pronouncements

are astonishing in their total lack of effect on the situation. However, they may

have served to create the public impression that something was being done. Indeed,

the impression created in the newspapers was that the problem was being resolved.

In an opinion piece in March of 1953 in an African American newspaper, California

Voice, Louie Campbell wrote,

We daren‚t let another week go by without calling our [readers‚]

attention to the marvelous clean-cut victory of the local branch of the NAACP over

the Oakland Fire Department in the matter of integrating colored firemen into the

department on an equal basis with other members.[∑] now the City Council has ordered

complete integration BEGINNING with the old station∑This concludes one of the greatest

victories of the local NAACP.š

This, unfortunately, was far from the truth. Internal statistics

from the department show that the transfers did not happen. This did not prevent

the mayor from trying to take credit for the supposed desegregation of the department:

An informant called last week to tell us that part of the credit

for the Oakland City Council‚s opening up the fire department to include Negroes

on a non-segregated basis should go to Mayor Clic Richell. Since he is running for

election to the town‚s newest office of permanent Mayor, we feel it would be the

opportune time to mention it now. őTis said that Mayor Rishell stretched his influence

to its limits in persuading the City Council to act favorably on the Fire Department

case. Seems odd that a man seeking re-election would keep so quiet about taking a

feature part in instituting good government within his city, but then we suppose

that‚s the kind of man he is. Anyway, the aforesaid informant gave us that impression∑.

This quote illustrates an interesting point about the government

of Oakland at the time. Both the city council and the mayor could proclaim how they

had helped to end segregation in the city, when they had no power to do so. In reality,

the only member of city government that had any say over the fire department was

the city manager, the highest administrator for all of the branches of the city government.

The city council did not have authority over the departments. As Oakland‚s Charter

reads, „The Council shall be the governing body of the City. It shall exercise the

corporate powers of the City and ∑it shall be vested with all powers of legislation.š

This is followed by the caveat that the Council „shall have no administrative powers.š

The Mayor is similarly without administrative power. According to the Charter:

The Mayor shall be the chief elective officer of the City∑he shall

recommend to the Council such legislation as he deems necessary∑he shall preside

over meetings of the Council, shall be the ceremonial head of the city, and shall

represent the City in intergovernmental relations as directed by the Council.

As was done for the City Council, the Charter spells out the lack

of power of the Mayor:

The Mayor shall have no administrative authority, it being the

intent of this Charter that the Mayor shall provide community leadership, while administrative

responsibilities are assigned to the City Manager.

So why were the City Council and the Mayor so eager to take the

credit for the supposed desegregation of the fire department? The answer is quite

simple. It was election time, and the African American vote was starting to become

important to those seeking office in the Oakland area. Demographics in Oakland had

changed radically during and after World War II. Oakland had grown by 82,000 people

in the period between 1940 and 1950. 8,462 African Americans had lived in Oakland

in 1940, while by 1950 that number had grown to 47,558. In terms of percentages,

the black population of Oakland grew from 3 percent in 1940 to 12 percent in 1950.

Fueling this boom in population were war industries vital to World War II. War industries

required more workers, far more than there had been in the area, attracting migrants

of all sorts into the Bay Area. Byron Rumford, one of the first black state assemblymen,

was elected from the 17th assembly district in 1948. In his district, which included

North and West Oakland, African Americans were 44 percent of the population by 1952.

African Americans were becoming increasingly more important in California politics,

so much so that in October 1952 during his presidential campaign, Dwight Eisenhower

stopped in areas of Northern California with substantial African American populations.

Other major presidential candidates also visited areas with large numbers of black

voters. As public opinion analyst Elmo Roper said, „The Negro community cannot be

ignored by the professional politicians who must take responsibility for engineering

victory or defeat.š For the mayor and the city council of Oakland, what easier way

could there be to solicit the black vote than to support a non-existent integration

proposal? For whatever reason, the problem appeared to be solved to those outside

the department, most importantly the local black press. If one takes the number of

articles about the Oakland Fire Department in California Voice as a barometer

of public opinion, it would appear that community leaders believed that segregation

in the fire department was no longer a problem. At this point the fight seemed to

peter out. Allen had been suspended, to the dismay of the black public, the NAACP,

and the firefighters of Station 22. Burke had pronounced his opinion in front of

the city manager and the mayor, who seemed unconcerned. The city council and the

mayor were willing to take credit for integration without actually causing it to

happen. The local newspapers were unable to see through the smokescreen of the department

spin and seemed content that the problem had been solved.

In the spring of 1953, the outlook for the firefighters of Station

22 must have been depressing. No further remedy from the City of Oakland was available.

However, Byron Rumford was pursuing the matter with State Attorney General Edmund

G. Brown, Sr.

Byron Rumford

Finally, in September 1954 came a pronouncement that put new life

into the struggle. At the request of Rumford, Brown issued an opinion on the following

question:

May a charter city through action of its administrative officers limit the assignment

of qualified civil service Negro firemen only to „all coloredš fire houses and refuse

to transfer them to „all whiteš fire houses?

The answer was unequivocal:

Maintenance of segregated Negro fire houses by a city is prohibited

under the provisions of both the State and Federal Constitutions. In the absence

of emergency, city officials, in carrying out discretionary authority in the assignment,

promotion and transfer of public employees, may not follow a policy of segregation

based on race and color.

The seventeen-page opinion systematically demolished from both

state and federal constitutional and case law perspectives all of the arguments that

were used to justify segregation in fire departments. Segregation, once regarded

as a necessity to preserve the harmony and effectiveness of the department, had become

a liability. Brown‚s opinion bluntly told the California fire service that segregation

would no longer be tolerated. The Attorney General‚s statement was the legal position

of the State of California, and while not legally binding, presented the viewpoint

of the state were such issues to come to trial. In this case, the opinion is quite

strong. The opinion had no less than 75 case citations from both federal and California

courts, and invoked both the state and federal constitutions in determining the illegality

of segregated fire houses. But couldn‚t a department decide what was best for its

city? Wouldn‚t integrating the department cause social problems among the firefighters?

Might not the city burn down while the firefighters were fighting each other in the

stations? Attorney General Brown addressed these arguments in his opinion:

For example, a city has some 85 fire houses. Two of these stations

are all Negro in their personnel, both as to men and officers. They are located in

predominantly Negro neighborhoods. The other fire houses are manned exclusively by

white personnel. The matter of assignment and transfer lies within the discretion

of the chief administrative officer of the fire department. In the past 14 years

Negroes have been assigned to fire houses manned only by colored firemen, none have

been assigned to „whiteš fire houses, and none have been allowed to transfer to the

so-called „whiteš fire houses. It is asserted, however, that such limitations are

not based upon race alone. It is pointed out that assignments are made with the purpose

of achieving the highest efficiency in the fire fighting service of the city, and

that morale and other factors indicate that efficiency will be higher if assignments

of white and Negro firemen are made upon a segregated basis.

Attorney General Brown was not convinced that „morale and other

factorsš would take precedence over the rights of the individual. On page 14 of the

opinion, he is quite explicit on this point:

Even though the administrative officer of a city‚s fire department

in a good faith use of his discretionary authority makes assignments and transfers

of colored employees on a segregated basis for the purpose of obtaining the highest

efficient operation of the city‚s fire-fighting units, such action∑would not be sustained

as a reasonable exercise of the city‚s police power when the result is to deprive

the colored firemen, on the basis of their race or color, equal opportunities to

engage and progress in their progression or work.

As for the legality of the policies of the department, Brown cited

the case of James v. Marinship Corporation in 1940. During the war, shipbuilding

became an important part of the Bay Area economy. African Americans were working

at jobs in the shipyards in Sausalito, but their jobs were threatened because the

shipyards had closed-shop labor contracts. The International Brotherhood of Boilermakers

would not admit black men as full union members. Although these workers had been

at the shipyard for over a year, when Marinship was informed the black skilled laborers

were not union members the corporation threatened to terminate their employment.

Marinship, owned by Bechtel, acknowledged that they had contracted with the United

States to operate the shipyards and that those contracts contained provisions forbidding

the discrimination against workers due to race or color, but argued that the problems

between the black shipbuilders and the Brotherhood were none of their business. The

Supreme Court of California ruled that the policy of Marinship Corporation was invalid.

Even though the corporation did not directly discriminate against the black employees

itself, their policies aided discriminatory practices. The James decision came to

be the decision by which racial discrimination in hiring and promotion could no longer

be permitted in California. Attorney General Brown‚s opinion states, „The decision

in that case leaves little doubt that discrimination because of race or color in

the field of public employment would have been enjoined under both the Federal and

California Constitutions.š The decision of James in 1944 meant that administrative

policies (i.e. Marinship‚s agreement with the International Brotherhood of Boilermakers)

that led to unequal hiring and promotional opportunities were not permitted.

Brown did not believe that Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka

applied to the situation of fire departments. In September of 1954 Brown was still

being hashed out and it was unclear what direction the law would take. Attorney General

Brown writes, „As the process of constitutional interpretation and application is

a case by case process, it remains to be seen to what extent the court will adjure

the application of the separate but equal doctrine to other phases of governmental

action∑After considering the decision in Brown, a federal district court in Maryland

has approved the continued application of the separate but equal doctrine to public

swimming pools where őreasonable grounds‚ existed for the separate treatment (Lonesome

v. Maxwell)š But even this case did not stand. Lonesome, decided on July 24, 1954,

was reversed in March 1955, just six months after Edmund Brown‚s opinion came out.

The Court of Appeals, in reversing the ruling, stated: „It is now obvious that segregation

cannot be justified as a means to preserve the public peace merely because the tangible

facilities furnished to one race are equal to those furnished to the other.š

The stage was set for the NAACP. Segregation in the fire departments

of California was not legally permissible. Attorney General Brown‚s opinion clearly

spelled out the legal tactics that would be the basis for lawsuits against fire department

that maintained segregated fire stations. The doctrine of „separate but equalš was

rapidly unraveling in the United States. Given these developments, a case against

the Oakland Fire Department would have easily been won. However, the NAACP never

filed suit. It appears that that they were simply waiting for the single event that

could result in the integration of the department: Chief Burke‚s 70th birthday.

The Oakland Fire Department was finally convinced that the segregation policy of

the department had to change. Still, no matter what legal weight could have been

brought to bear on the department, desegregation boiled down to one event: Chief

Burke turned 70, the compulsory age of retirement in the Oakland Fire Department.

He retired on July 1, 1955 and was replaced by Chief James Sweeney, a man with a

long career in the Oakland Fire Department whose father had once been the fire marshal

for the city. Within two months of the appointment of Chief Sweeney, the long-awaited

transfers began to come. Firefighters all over the city were transferred to different

stations, and segregation finally came to an end.

The integration of the department was quickly done, but it took

some time for the African American firefighters to be accepted. Life was not easy

for the black firefighters. Samuel Golden recalled the early days of desegregation:

It was August 5, 1955, that was the day they integrated and I went

to 29 Engine. The first day I went there, I checked in with the captain. The captain

called me into his office and told me what I could do and what I couldn't do. One

of the things I couldn't do was eat with them. I had to bring my own mattress out

and sleep on the watch bed whenever I was on watch. We were told that we had a special

bed that we were sleeping in. There was another black firefighter on the other shift,

and we both slept in the same bed.

Oakland was one of the first fire departments in the United States

to desegregate, but surprisingly, no violence was reported. Instead, the black firefighters

were ignored by many of the white firefighters, who did their best to exclude their

new co-workers from station life. Like in many things, change came slowly. Golden

went on to explain the gradual thawing of the department:

Everybody trusted everybody at the fire scene, and everybody did

their job. There was no quibbling about it. If the officer gave you an order to go

in here and fight the fire - it would be maybe one black and one white - you'd be

on the hose together. There was no problem there. It was just that when you got back

in the fire station the problems started. They didn't want to socialize with you

there. But at a fire it was different∑

The younger firefighters' attitude was a lot different than some

of the older firefighters. They started talking to us as they came in. They socialized

with us more than the older firefighters did. As more of them came into the department,

the attitudes began to change.

By the time Golden became chief of the department, attitudes had

drastically changed. Royal Towns was in the department long enough to experience

what would have been unthinkable in 1950:

This boy [Samuel Golden] who is the Chief of the Fire Department

now, he was one of my boy scouts. I quit the fire department a month early so he‚d

get a lieutenant‚s job in the fire department. And now, he‚s the Chief of the Fire

Department, black man. And I went to his reception and two white fellas came up and

they kissed me, both of them were battalion chiefs∑

I says, „Why all this personal infatuation?š

So one fella told me, he says, „You know, Royal, you taught me

something about the fire department that I‚ve used all through the fire department.š

And I said, „What was that?š

And he said, „That‚s őreflections‚∑when we first came here, we

were the first whites that were mixed in with a black company. And you told me, őNow,

everything in life is a reflection. If you‚re nice to people, they‚re nice to you.

If you‚re nasty to people, they‚re nasty to you.‚ And so forth and so on.š

„Anyway,š he says, „I used that all throughout the fire department.š∑

So that‚s the way. They reflected.

Desegregation of the Oakland Fire Department left a lasting legacy.

It was an important event in Oakland‚s history, the beginning of the change in status

of African Americans in Oakland. Once outsiders, fighting for a place at the table,

Oakland‚s black citizens transformed not only the fire department but the city government

as well. But it was not just the fire department that benefited from the change.

The desegregation of the Oakland Fire Department had wider effects on black leadership

in the city of Oakland. Once a attorney for the NAACP and later the first black mayor

of Oakland, Mayor Lionel Wilson reflected on his pivotal experience of the Oakland

Fire Department case in an interview conducted in his office in City Hall in 1985:

But what I mean is that I didn't realize the impact that these

experiences, the discriminatory practices and segregation and so forth, had had on

me until after I had, in later years, begun to reflect on why I had such a tremendous

drive to work in the community and work with the NAACP∑In my law practice I ran a

legal aid office for people who couldn‚t afford services. Then I realizedųI guess

it was the impact from what I had experienced throughout the years.

I suppose that the culmination of it, in one sense, was my role

as chairman of the Legal Redress Committee and walking into this very same office

with this very same desk sitting there, meeting with the mayor and the city manager

and the fire chief, to try and convince them that they ought to eliminate the segregated

fire department.

In 1991, approximately 43 percent of firefighters in the Oakland Fire Department

were people of color. The implications for the Oakland Fire Department go farther

than the inclusion of African Americans into the department. The desegregation of

the department was not simply a shift in personnel, but a dramatic shift in the culture

of the fire department that led to the inclusion of all kinds of people into the

family of the fire service. Deputy Chief Ernest Robinson sums up the change for the

department:

Not only are we heroes - people talk about firefighters being heroes

all the timeųbut more importantly, we need to be role models so when we look out

in the community and we see the children of different ethnicities, of both genders,

who one day say "I want to be a firefighter," it makes that dream more

of a realityųseeing someone in that fire engine who looks like them.